Zaregistrujte si v komentech vybranou povidku!

23. listopadu 2020

Shakespeare!

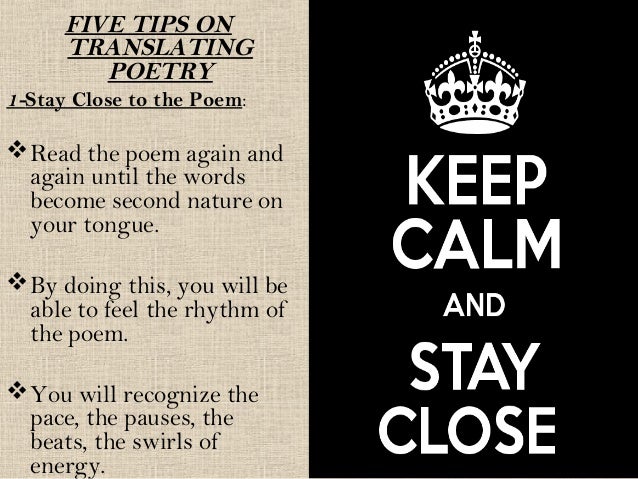

Jak překládat poezii? A překládat ji vůbec? Má přednost forma či obsah? Dají se na překlad poesie aplikovat pravidla, o kterých jsme mluvili?

1. Projděte si komentáře k tomuto vstupu. Jaké typy básnické tvorby se objevují? Mají něco společného?

Dokážete se během 2 minut naučit 4 libovolné řádky zpaměti? Jak postupujete?

2. Stáhněte si z capsy soubor s různými verzemi překladu Shakespearova sonetu.

Shakespeare_Sonet66_13prekladu.doc

Která verze se vám nejvíc líbí? Proč? Napište svůj názor do komentáře k tomuto blogu. Uvažujete nad formou a obsahem nebo více nasloucháte svým pocitům?

Sonet 66 English

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4MWBW_c7Fsw

Sonet 66 Hilský

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SJw5BQba7zQ

Interview s Martinem Hilskym

__________________________________

3. Přečtěte si pomalu a klidně následující sonet. Vnímejte rytmus a zvukomalbu textu, při druhém čtení se teprve víc soustřeďte na obsah.

Pokuste se přeložit jedno ze tří čtyřverší + poslání.

Rozmyslete si, jak budete postupovat.

audio

_______________________

originál

https://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/views/sonnets/sonnets.php

české překlady Shakespeara

Jan Vladislav-pdf

http://lukaflek.wz.cz/poems/ws_sonet29.htm

http://www.v-art.cz/taxus_bohemica/eh/bergrova.htm

http://www.shakespearovy-sonety.cz/a29/

Hilsky sonet 12 youtube

http://sonety.blog.cz/0803/william-shakespeare-sonnet-12-64-73-94-107-128-sest-sonetu-v-mem-prekladu

https://ucbcluj.org/current-issue/vol-21-spring-2012/2842-2/

http://mikechasar.blogspot.cz/2011/02/gi-jane-dh-lawrence.html

________________

https://lyricstranslate.com/en/sonnet-66-soneto-66.html

Soneto 66

Harto de todo esto, muerte pido y paz:

de ver cómo es el mérito mendigo nato

y ver alzada en palmas la vil nulidad

y la más pura fe sufrir perjurio ingrato

y la dorada honra con deshonra dada

y el virginal pudor brutalmente arrollado

y cabal derechura a tuerto estropeada

y por cojera el brío juvenil quebrado

y el arte amordazado por la autoridad

y el genio obedeciendo a un docto mequetrefe

y llamada simpleza la simple verdad

y un buen cautivo sometido a un triste jefe;

harto de todo esto; de esto huiría; sólo

que, al morir, a mi amor aquí lo dejo solo.

__________________

https://lyricstranslate.com/en/sonnet-66-shakespeare-sonett-66.html

Shakespeare: Sonett 66

Satt hab ich all dies, verlang im Tod den Frieden,

Seh ich, dass das Verdienst ein Bettler bleibt,

Dass nacktem Nichts das Festagskleid beschieden,

Dass Meineid reinste Treu ins Unglück treibt,

Dass Schande sich mit Ehrengold umhängt,

Dass Geilheit alles, was noch rein ist, schändet,

Dass Unrecht die Gerechtigkeit verdrängt,

Dass Stärke, durch Gewalt gelähmt, verkrüppelt,

Dass Macht dem Wissen fest die Zunge bindet,

Dass Dummheit kritisch Können überwacht,

Dass man die lautre Wahrheit lachhaft findet,

Dass Gut als Sklave dient der bösen Macht.

Satt hab' ich all dies, möcht' weg von alldem sein,

Doch wär' ich tot, ließ' ich mein Lieb allein.

https://shine.unibas.ch/Sonette1.htm#66

https://lyricstranslate.com/en/sonnet-66-sonett-66.html#songtranslation

__________________

Sonett 66

Des Todes Ruh' ersehn' ich lebensmüd,

Seh' ich Verdienst als Bettler auf der Welt,

Und leeres Nichts zu höchstem Prunk erblüht,

Und reinste Treue, die im Meineid fällt,

Und goldne Ehre, die die Schande schmückt,

Und Mädchenunschuld roh dahingeschlachtet,

Und Kraft durch schwache Leitung unterdrückt,

Und echte Hoheit ungerecht verachtet,

Und Kunst geknebelt durch die Übermacht,

Und Unsinn herrschend auf der Weisheit Thron,

Und Einfalt als Einfältigkeit verlacht,

Und Knecht das Gute in des Bösen Fron,

Ja lebensmüd entging' ich gern der Pein,

Ließ den Geliebten nicht mein Tod allein.

Übersetzt von Max Josef Wolff

https://lyricstranslate.com/en/sonnet-66-sonett-66.html-0#songtranslation

__________________

Sonett 66

Ich hab es satt. Wär ich ein toter Mann.

Wenn Würde schon zur Bettelei geborn

Und Nichtigkeit sich ausstaffieren kann

Und jegliches Vertrauen ist verlorn

Und Rang und Name Fähigkeit entbehrt

Und Fraun vergebens sich der Männer wehren

Und wenn der Könner Gnadenbrot verzehrt

Und Duldende nicht aufbegehren

Und Kunst gegängelt von der Obrigkeit

Und Akademiker erklärn den Sinn

Und simples Zeug tritt man gelehrsam breit

Und Gut und Böse biegt sich jeder hin

Ich hab es satt. Ich möchte wegsein, bloß:

Noch liebe ich. Und das läßt mich nicht los.

Deutsche Fassung von

Karl Werner Plath

__________________

Сонет 66

Измучась всем, я умереть хочу.

Тоска смотреть, как мается бедняк,

И как шутя живется богачу,

И доверять, и попадать впросак,

И наблюдать, как наглость лезет в свет,

И честь девичья катится ко дну,

И знать, что ходу совершенствам нет,

И видеть мощь у немощи в плену,

И вспоминать, что мысли заткнут рот,

И разум сносит глупости хулу,

И прямодушье простотой слывет,

И доброта прислуживает злу.

Измучась всем, не стал бы жить и дня,

Да другу будет трудно без меня.

Pasternak, Boris Leonidovic

__________________

Sonnet 66: Translation to modern English

Exhausted with the following things I cry out for releasing death: for example, seeing a deserving person who has been born into poverty; and an undeserving one dressed in the finest clothes; and someone who shows trustworthiness wretchedly betrayed; and public honour shamefully bestowed on the unfit; and unblemished goodness forced into bad ways; and genuine perfection unjustly disgraced; and conviction crippled by corruption; and skill suppressed by those with the power to do it; and stupidity restraining the advance of knowledge; and simple truth being dismissed as simplistic; and good taking orders from evil. Exhausted with all these things I want to escape, except that by dying I would be abandoning my love.

9. listopadu 2020

Strašidlo Cantervillské

by Oscar Wilde

II

The day had been warm and sunny; and, in the cool of the evening, the whole family went out to drive. They did not return home till nine o'clock, when they had a light supper. The conversation in no way turned upon ghosts, so there were not even those primary conditions of receptive expectations which so often precede the presentation of psychical phenomena. The subjects discussed, as I have since learned from Mr. Otis, were merely such as form the ordinary conversation of cultured Americans of the better class, such as the immense superiority of Miss Fanny Devonport over Sarah Bernhardt as an actress; the difficulty of obtaining green corn, buckwheat cakes, and hominy, even in the best English houses; the importance of Boston in the development of the world-soul; the advantages of the baggage-check system in railway travelling; and the sweetness of the New York accent as compared to the London drawl. No mention at all was made of the supernatural, nor was Sir Simon de Canterville alluded to in any way. At eleven o'clock the family retired, and by half-past all the lights were out. Some time after, Mr. Otis was awakened by a curious noise in the corridor, outside his room. It sounded like the clank of metal, and seemed to be coming nearer every moment. He got up at once, struck a match, and looked at the time. It was exactly one o'clock. He was quite calm, and felt his pulse, which was not at all feverish. The strange noise still continued, and with it he heard distinctly the sound of footsteps. He put on his slippers, took a small oblong phial out of his dressing-case, and opened the door. Right in front of him he saw, in the wan moonlight, an old man of terrible aspect. His eyes were as red burning coals; long grey hair fell over his shoulders in matted coils; his garments, which were of antique cut, were soiled and ragged, and from his wrists and ankles hung heavy manacles and rusty gyves.

"My dear sir," said Mr. Otis, "I really must insist on your oiling those chains, and have brought you for that purpose a small bottle of the Tammany Rising Sun Lubricator. It is said to be completely efficacious upon one application, and there are several testimonials to that effect on the wrapper from some of our most eminent native divines. I shall leave it here for you by the bedroom candles, and will be happy to supply you with more, should you require it." With these words the United States Minister laid the bottle down on a marble table, and, closing his door, retired to rest.

For a moment the Canterville ghost stood quite motionless in natural indignation; then, dashing the bottle violently upon the polished floor, he fled down the corridor, uttering hollow groans, and emitting a ghastly green light. Just, however, as he reached the top of the great oak staircase, a door was flung open, two little white-robed figures appeared, and a large pillow whizzed past his head! There was evidently no time to be lost, so, hastily adopting the Fourth dimension of Space as a means of escape, he vanished through the wainscoting, and the house became quite quiet.

On reaching a small secret chamber in the left wing, he leaned up against a moonbeam to recover his breath, and began to try and realize his position. Never, in a brilliant and uninterrupted career of three hundred years, had he been so grossly insulted. He thought of the Dowager Duchess, whom he had frightened into a fit as she stood before the glass in her lace and diamonds; of the four housemaids, who had gone into hysterics when he merely grinned at them through the curtains on one of the spare bedrooms; of the rector of the parish, whose candle he had blown out as he was coming late one night from the library, and who had been under the care of Sir William Gull ever since, a perfect martyr to nervous disorders; and of old Madame de Tremouillac, who, having wakened up one morning early and seen a skeleton seated in an armchair by the fire reading her diary, had been confined to her bed for six weeks with an attack of brain fever, and, on her recovery, had become reconciled to the Church, and broken off her connection with that notorious sceptic, Monsieur de Voltaire. He remembered the terrible night when the wicked Lord Canterville was found choking in his dressing-room, with the knave of diamonds half-way down his throat, and confessed, just before he died, that he had cheated Charles James Fox out of £50,000 at Crockford's by means of that very card, and swore that the ghost had made him swallow it. All his great achievements came back to him again, from the butler who had shot himself in the pantry because he had seen a green hand tapping at the window-pane, to the beautiful Lady Stutfield, who was always obliged to wear a black velvet band round her throat to hide the mark of five fingers burnt upon her white skin, and who drowned herself at last in the carp-pond at the end of the King's Walk. With the enthusiastic egotism of the true artist, he went over his most celebrated performances, and smiled bitterly to himself as he recalled to mind his last appearance as "Red Reuben, or the Strangled Babe," his _début_ as "Guant Gibeon, the Blood-sucker of Bexley Moor," and the _furore_ he had excited one lovely June evening by merely playing ninepins with his own bones upon the lawn-tennis ground. And after all this some wretched modern Americans were to come and offer him the Rising Sun Lubricator, and throw pillows at his head! It was quite unbearable. Besides, no ghost in history had ever been treated in this manner. Accordingly, he determined to have vengeance, and remained till daylight in an attitude of deep thought.

Stylové roviny

Nápověda:

výrazy archaické x neologismy

pejorativa x diminutiva

emočně negativní x pozitivní

slang a argot x odborná terminologie...

Série synonym najdete například zde:

http://prekladanipvk.blogspot.cz/2016/02/synonymie-stylove-roviny.html

http://prekladanipvk.blogspot.cz/2014/10/stylove-roviny.html

23. října 2020

Modest Proposal

1. Co víte o tomto díle?

2. Jak byste charakterizovali autorský styl?

____________________________________

A MODEST PROPOSAL

For preventing the children of poor people in Ireland, from being a burden on their parents or country, and for making them beneficial to the publick.

by Dr. Jonathan Swift 1729

It is a melancholy object to those, who walk through this great town, or travel in the country, when they see the streets, the roads and cabbin-doors crowded with beggars of the female sex, followed by three, four, or six children, all in rags, and importuning every passenger for an alms. These mothers instead of being able to work for their honest livelihood, are forced to employ all their time in stroling to beg sustenance for their helpless infants who, as they grow up, either turn thieves for want of work, or leave their dear native country, to fight for the Pretender in Spain, or sell themselves to the Barbadoes.

I think it is agreed by all parties, that this prodigious number of children in the arms, or on the backs, or at the heels of their mothers, and frequently of their fathers, is in the present deplorable state of the kingdom, a very great additional grievance; and therefore whoever could find out a fair, cheap and easy method of making these children sound and useful members of the common-wealth, would deserve so well of the publick, as to have his statue set up for a preserver of the nation.

But my intention is very far from being confined to provide only for the children of professed beggars: it is of a much greater extent, and shall take in the whole number of infants at a certain age, who are born of parents in effect as little able to support them, as those who demand our charity in the streets.

As to my own part, having turned my thoughts for many years, upon this important subject, and maturely weighed the several schemes of our projectors, I have always found them grossly mistaken in their computation. It is true, a child just dropt from its dam, may be supported by her milk, for a solar year, with little other nourishment: at most not above the value of two shillings, which the mother may certainly get, or the value in scraps, by her lawful occupation of begging; and it is exactly at one year old that I propose to provide for them in such a manner, as, instead of being a charge upon their parents, or the parish, or wanting food and raiment for the rest of their lives, they shall, on the contrary, contribute to the feeding, and partly to the cloathing of many thousands.

There is likewise another great advantage in my scheme, that it will prevent those voluntary abortions, and that horrid practice of women murdering their bastard children, alas! too frequent among us, sacrificing the poor innocent babes, I doubt, more to avoid the expence than the shame, which would move tears and pity in the most savage and inhuman breast.

The number of souls in this kingdom being usually reckoned one million and a half, of these I calculate there may be about two hundred thousand couple whose wives are breeders; from which number I subtract thirty thousand couple, who are able to maintain their own children, (although I apprehend there cannot be so many, under the present distresses of the kingdom) but this being granted, there will remain an hundred and seventy thousand breeders. I again subtract fifty thousand, for those women who miscarry, or whose children die by accident or disease within the year. There only remain an hundred and twenty thousand children of poor parents annually born. The question therefore is, How this number shall be reared, and provided for? which, as I have already said, under the present situation of affairs, is utterly impossible by all the methods hitherto proposed. For we can neither employ them in handicraft or agriculture; we neither build houses, (I mean in the country) nor cultivate land: they can very seldom pick up a livelihood by stealing till they arrive at six years old; except where they are of towardly parts, although I confess they learn the rudiments much earlier; during which time they can however be properly looked upon only as probationers: As I have been informed by a principal gentleman in the county of Cavan, who protested to me, that he never knew above one or two instances under the age of six, even in a part of the kingdom so renowned for the quickest proficiency in that art.

I am assured by our merchants, that a boy or a girl before twelve years

old, is no saleable commodity, and even when they come to this age, they

will not yield above three pounds, or three pounds and half a crown

at most, on the exchange; which cannot turn to account either to the

parents or kingdom, the charge of nutriments and rags having been at

least four times that value.

I shall now therefore humbly propose my own thoughts, which I hope will

not be liable to the least objection.

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in

London, that a young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old, a

most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted,

baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a

fricasie, or a ragoust.

I do therefore humbly offer it to publick consideration, that of the

hundred and twenty thousand children, already computed, twenty thousand

may be reserved for breed, whereof only one fourth part to be males;

which is more than we allow to sheep, black cattle, or swine, and my

reason is, that these children are seldom the fruits of marriage, a

circumstance not much regarded by our savages, therefore, one male will

be sufficient to serve four females. That the remaining hundred thousand

may, at a year old, be offered in sale to the persons of quality and

fortune, through the kingdom, always advising the mother to let them

suck plentifully in the last month, so as to render them plump, and fat

for a good table. A child will make two dishes at an entertainment for

friends, and when the family dines alone, the fore or hind quarter will

make a reasonable dish, and seasoned with a little pepper or salt, will

be very good boiled on the fourth day, especially in winter.

I have reckoned upon a medium, that a child just born will weigh 12

pounds, and in a solar year, if tolerably nursed, encreaseth to 28

pounds.

I grant this food will be somewhat dear, and therefore very proper for

landlords, who, as they have already devoured most of the parents, seem

to have the best title to the children.

Infant's flesh will be in season throughout the year, but more plentiful

in March, and a little before and after; for we are told by a grave

author, an eminent French physician, that fish being a prolifick dyet,

there are more children born in Roman Catholick countries about nine

months after Lent, the markets will be more glutted than usual, because

the number of Popish infants, is at least three to one in this kingdom,

and therefore it will have one other collateral advantage, by lessening

the number of Papists among us.

I have already computed the charge of nursing a beggar's child (in which

list I reckon all cottagers, labourers, and four-fifths of the farmers)

to be about two shillings per annum, rags included; and I believe no

gentleman would repine to give ten shillings for the carcass of a good

fat child, which, as I have said, will make four dishes of excellent

nutritive meat, when he hath only some particular friend, or his

own family to dine with him. Thus the squire will learn to be a good

landlord, and grow popular among his tenants, the mother will have eight

shillings neat profit, and be fit for work till she produces another

child.

Those who are more thrifty (as I must confess the times require) may

flea the carcass; the skin of which, artificially dressed, will make

admirable gloves for ladies, and summer boots for fine gentlemen.

As to our City of Dublin, shambles may be appointed for this purpose, in

the most convenient parts of it, and butchers we may be assured will not

be wanting; although I rather recommend buying the children alive, and

dressing them hot from the knife, as we do roasting pigs.

A very worthy person, a true lover of his country, and whose virtues

I highly esteem, was lately pleased, in discoursing on this matter, to

offer a refinement upon my scheme. He said, that many gentlemen of this

kingdom, having of late destroyed their deer, he conceived that the

want of venison might be well supply'd by the bodies of young lads and

maidens, not exceeding fourteen years of age, nor under twelve; so great

a number of both sexes in every country being now ready to starve for

want of work and service: And these to be disposed of by their parents

if alive, or otherwise by their nearest relations. But with due

deference to so excellent a friend, and so deserving a patriot, I

cannot be altogether in his sentiments; for as to the males, my American

acquaintance assured me from frequent experience, that their flesh was

generally tough and lean, like that of our school-boys, by continual

exercise, and their taste disagreeable, and to fatten them would not

answer the charge. Then as to the females, it would, I think, with

humble submission, be a loss to the publick, because they soon would

become breeders themselves: And besides, it is not improbable that some

scrupulous people might be apt to censure such a practice, (although

indeed very unjustly) as a little bordering upon cruelty, which, I

confess, hath always been with me the strongest objection against any

project, how well soever intended.

But in order to justify my friend, he confessed, that this expedient

was put into his head by the famous Salmanaazor, a native of the island

Formosa, who came from thence to London, above twenty years ago, and in

conversation told my friend, that in his country, when any young person

happened to be put to death, the executioner sold the carcass to persons

of quality, as a prime dainty; and that, in his time, the body of a

plump girl of fifteen, who was crucified for an attempt to poison the

Emperor, was sold to his imperial majesty's prime minister of state, and

other great mandarins of the court in joints from the gibbet, at four

hundred crowns. Neither indeed can I deny, that if the same use were

made of several plump young girls in this town, who without one single

groat to their fortunes, cannot stir abroad without a chair, and appear

at a play-house and assemblies in foreign fineries which they never will

pay for; the kingdom would not be the worse.

Some persons of a desponding spirit are in great concern about that vast

number of poor people, who are aged, diseased, or maimed; and I have

been desired to employ my thoughts what course may be taken, to ease

the nation of so grievous an incumbrance. But I am not in the least pain

upon that matter, because it is very well known, that they are every day

dying, and rotting, by cold and famine, and filth, and vermin, as fast

as can be reasonably expected. And as to the young labourers, they

are now in almost as hopeful a condition. They cannot get work, and

consequently pine away from want of nourishment, to a degree, that if

at any time they are accidentally hired to common labour, they have not

strength to perform it, and thus the country and themselves are happily

delivered from the evils to come.

I have too long digressed, and therefore shall return to my subject. I

think the advantages by the proposal which I have made are obvious and

many, as well as of the highest importance.

For first, as I have already observed, it would greatly lessen the

number of Papists, with whom we are yearly over-run, being the principal

breeders of the nation, as well as our most dangerous enemies, and who

stay at home on purpose with a design to deliver the kingdom to the

Pretender, hoping to take their advantage by the absence of so many good

Protestants, who have chosen rather to leave their country, than stay at

home and pay tithes against their conscience to an episcopal curate.

Secondly, The poorer tenants will have something valuable of their own,

which by law may be made liable to a distress, and help to pay their

landlord's rent, their corn and cattle being already seized, and money a

thing unknown.

Thirdly, Whereas the maintainance of an hundred thousand children,

from two years old, and upwards, cannot be computed at less than

ten shillings a piece per annum, the nation's stock will be thereby

encreased fifty thousand pounds per annum, besides the profit of a

new dish, introduced to the tables of all gentlemen of fortune in the

kingdom, who have any refinement in taste. And the money will circulate

among our selves, the goods being entirely of our own growth and

manufacture.

Fourthly, The constant breeders, besides the gain of eight shillings

sterling per annum by the sale of their children, will be rid of the

charge of maintaining them after the first year.

Fifthly, This food would likewise bring great custom to taverns,

where the vintners will certainly be so prudent as to procure the best

receipts for dressing it to perfection; and consequently have their

houses frequented by all the fine gentlemen, who justly value themselves

upon their knowledge in good eating; and a skilful cook, who understands

how to oblige his guests, will contrive to make it as expensive as they

please.

Sixthly, This would be a great inducement to marriage, which all wise

nations have either encouraged by rewards, or enforced by laws and

penalties. It would encrease the care and tenderness of mothers towards

their children, when they were sure of a settlement for life to the

poor babes, provided in some sort by the publick, to their annual profit

instead of expence. We should soon see an honest emulation among the

married women, which of them could bring the fattest child to the

market. Men would become as fond of their wives, during the time of

their pregnancy, as they are now of their mares in foal, their cows in

calf, or sow when they are ready to farrow; nor offer to beat or kick

them (as is too frequent a practice) for fear of a miscarriage.

Many other advantages might be enumerated. For instance, the addition

of some thousand carcasses in our exportation of barrel'd beef: the

propagation of swine's flesh, and improvement in the art of making good

bacon, so much wanted among us by the great destruction of pigs,

too frequent at our tables; which are no way comparable in taste or

magnificence to a well grown, fat yearly child, which roasted whole will

make a considerable figure at a Lord Mayor's feast, or any other publick

entertainment. But this, and many others, I omit, being studious of

brevity.

Supposing that one thousand families in this city, would be constant

customers for infants flesh, besides others who might have it at merry

meetings, particularly at weddings and christenings, I compute that

Dublin would take off annually about twenty thousand carcasses; and the

rest of the kingdom (where probably they will be sold somewhat cheaper)

the remaining eighty thousand.

I can think of no one objection, that will possibly be raised against

this proposal, unless it should be urged, that the number of people will

be thereby much lessened in the kingdom. This I freely own, and 'twas

indeed one principal design in offering it to the world. I desire the

reader will observe, that I calculate my remedy for this one individual

Kingdom of Ireland, and for no other that ever was, is, or, I think,

ever can be upon Earth. Therefore let no man talk to me of other

expedients: Of taxing our absentees at five shillings a pound: Of using

neither cloaths, nor houshold furniture, except what is of our

own growth and manufacture: Of utterly rejecting the materials and

instruments that promote foreign luxury: Of curing the expensiveness of

pride, vanity, idleness, and gaming in our women: Of introducing a vein

of parsimony, prudence and temperance: Of learning to love our

country, wherein we differ even from Laplanders, and the inhabitants

of Topinamboo: Of quitting our animosities and factions, nor acting any

longer like the Jews, who were murdering one another at the very moment

their city was taken: Of being a little cautious not to sell our country

and consciences for nothing: Of teaching landlords to have at least one

degree of mercy towards their tenants. Lastly, of putting a spirit of

honesty, industry, and skill into our shop-keepers, who, if a resolution

could now be taken to buy only our native goods, would immediately unite

to cheat and exact upon us in the price, the measure, and the goodness,

nor could ever yet be brought to make one fair proposal of just dealing,

though often and earnestly invited to it.

Therefore I repeat, let no man talk to me of these and the like

expedients, 'till he hath at least some glympse of hope, that there will

ever be some hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.

But, as to my self, having been wearied out for many years with offering

vain, idle, visionary thoughts, and at length utterly despairing of

success, I fortunately fell upon this proposal, which, as it is wholly

new, so it hath something solid and real, of no expence and little

trouble, full in our own power, and whereby we can incur no danger

in disobliging England. For this kind of commodity will not bear

exportation, and flesh being of too tender a consistence, to admit a

long continuance in salt, although perhaps I could name a country, which

would be glad to eat up our whole nation without it.

After all, I am not so violently bent upon my own opinion, as to reject

any offer, proposed by wise men, which shall be found equally innocent,

cheap, easy, and effectual. But before something of that kind shall be

advanced in contradiction to my scheme, and offering a better, I desire

the author or authors will be pleased maturely to consider two points.

First, As things now stand, how they will be able to find food and

raiment for a hundred thousand useless mouths and backs. And secondly,

There being a round million of creatures in humane figure throughout

this kingdom, whose whole subsistence put into a common stock, would

leave them in debt two million of pounds sterling, adding those who are

beggars by profession, to the bulk of farmers, cottagers and labourers,

with their wives and children, who are beggars in effect; I desire

those politicians who dislike my overture, and may perhaps be so bold

to attempt an answer, that they will first ask the parents of these

mortals, whether they would not at this day think it a great happiness

to have been sold for food at a year old, in the manner I prescribe, and

thereby have avoided such a perpetual scene of misfortunes, as they have

since gone through, by the oppression of landlords, the impossibility of

paying rent without money or trade, the want of common sustenance, with

neither house nor cloaths to cover them from the inclemencies of the

weather, and the most inevitable prospect of intailing the like, or

greater miseries, upon their breed for ever.

I profess, in the sincerity of my heart, that I have not the least

personal interest in endeavouring to promote this necessary work, having

no other motive than the publick good of my country, by advancing

our trade, providing for infants, relieving the poor, and giving some

pleasure to the rich. I have no children, by which I can propose to

get a single penny; the youngest being nine years old, and my wife past

child-bearing.

19. října 2020

Co se může

„Překlad může být

věrný nebo krásný.“

Překladatelé nazývají jazyk originálu též výchozím jazykem a

jazyk překladu cílovým jazykem."

Iuvenes translatores

INFORMACE = fakta + emoce

Autor – představa 1 – text 1 – čtenář – představa 2

Autor – představa 1 – text 1 – čtenář = překladatel – představa 2 –

text2 – čtenář – představa 3

Překladatelské rozhodování (Levý str. 33)

- Překlad musí reprodukovat slova/ideje originálu.

- Překlad se má číst jako originál/jako překlad.

- Překlad má odrážet styl autora/překladatele.

- Překlad by měl mít kvality textu náležejícího do doby originálu/do doby překladu.

- Překladatel může/nemůže k originálu nic přidávat.

- Překladatel může/nemůže z originálu nic vynechávat.

12. října 2020

Hailey - Hotel

Klasická americká populární literatura :) a docela obyčejný jazyk. Jenže - mezi mluvčími najdete bělochy i černochy, Američany i Francouze. Každý mluví trochu jinak.

A prostředí hotelové kuchyně může skýtat řadu pastí v podobě odborných termínů a slangových výrazů.

Přečtete si nejprve CELÝ úryvek, zvykněte si na jednající postavy. Pak si udělejte jejich seznam. Kdo je v hotelu kdo, jaké má povinnosti a postavení, je černý nebo bílý? Pokud nevíte jiste, pročtěte si anglický originál (k dispozici na capse). Pak se teprv pusťte do překladu.

Arthur Hailey - Hotel

Chapter 8

___________

Peter nodded agreeably to Max, the head

waiter, who hurried forward.

“Good day, Mr. McDermott. A table by

yourself?”

“No, I’ll join the penal colony.” Peter seldom

exercised his privilege, as assistant general manager, of occupying a table of

his own in the dining room. Most days he preferred to join other executive

staff members at the large circular table reserved for their use near the

kitchen door.

The St. Gregory’s comptroller, Royall Edwards,

and Sam Jakubiec, the stocky, balding credit manager, were already at lunch as

Peter joined them. Doc Vickery, the chief engineer, who had arrived a few

minutes earlier, was studying a menu. Slipping into the chair which Max held

out, Peter inquired, “What looks good?”

“Try the watercress soup,” Jakubiec advised

between sips of his own. “It’s not like any mother made; it’s a damn sight

better.”

Royall Edwards added in his precise

accountant’s voice, “The special today is fried chicken. We have that coming.”

As the head waiter left, a young table waiter

appeared swiftly beside them. Despite standing instructions to the contrary,

the executives’ self-styled penal colony invariably received the best service

in the dining room. It was hard—as Peter and others had discovered in the

past—to persuade employees that the hotel’s paying customers were more

important than the executives who ran the hotel.

The chief engineer closed his menu, peering

over his thick-rimmed spectacles which had slipped, as usual, to the tip of his

nose. “The same’ll do for me, sonny.”

“I’ll make it unanimous.” Peter handed back

the menu which he had not opened.

The waiter hesitated. “I’m not sure about the

fried chicken, sir. You might prefer something else.”

“Well,” Jakubiec said, “now’s a fine time to

tell us that.”

“I can change your order easily, Mr. Jakubiec.

Yours too, Mr. Edwards.”

Peter asked, “What’s wrong with the fried

chicken?”

“Maybe I shouldn’t have said.” The waiter

shifted uncomfortably. “Fact is, we’ve been getting complaints. People don’t

seem to like it.” Momentarily he turned his head, eyes ranging the busy dining

room.

“In that case,” Peter told him, “I’m curious

to know why. So leave my order the way it is.” A shade reluctantly, the others

nodded agreement.

When the waiter had gone, Jakubiec asked,

“What’s this rumor I hear—that our dentists’ convention may walk out?”

“Your hearing’s good, Sam. This afternoon I’ll

know whether it remains a rumor.” Peter began his soup, which had appeared like

magic, then described the lobby fracas of an hour earlier. The faces of the

others grew serious as they listened.

Royall Edwards remarked, “It has been my

observation on disasters that they seldom occur singly. Judging by our

financial results lately—which you gentlemen are aware of—this could merely be

one more.”

“If it turns out that way,” the chief engineer

observed, “nae doubt the first thing ye’ll do is lop some muir from

engineering’s budget.”

“Either that,” the comptroller rejoined, “or

eliminate it entirely.”

The chief grunted, unamused.

“Maybe we’ll all be eliminated,” Sam Jakubiec

said. “If the O’Keefe crowd take over.” He looked inquiringly at Peter, but

Royall Edwards gave a cautioning nod as their waiter returned. The group

remained silent as the young man deftly served the comptroller and credit

manager while, around them, the hum of the dining room, a subdued clatter of

plates and the passage of waiters through the kitchen door, continued.

When the waiter had gone, Jakubiec asked

pointedly, “Well, what is the news?”

Peter shook his head. “Don’t know a thing,

Sam. Except that was darn good soup.”

“If you remember,” Royall Edwards said, “we

recommended it, and I will now offer you some more well-founded advice—quit

while you’re ahead.” He had been sampling the fried chicken served to himself

and Jakubiec a moment earlier. Now he put down his knife and fork. “Another

time I suggest we listen more respectfully to our waiter.”

Peter asked, “Is it really that bad?”

“I suppose not,” the comptroller said. “If you

happen to be partial to rancid food.”

Dubiously, Jakubiec sampled his own serving as

the others watched. At length he informed them: “Put it this way. If I were

paying for this meal—I wouldn’t.”

“No, Mr. McDermott, I understand he’s ill.

Sous-chef Lemieux is in charge.” The head waiter said anxiously, “If it’s about

the fried chicken, I assure you everything is taken care of. We’ve stopped

serving that dish and where there have been complaints the entire meal has been

replaced.” His glance went to the table. “We’ll do the same thing here at

once.”

“At the moment,” Peter said, “I’m more

concerned about finding out what happened. Would you ask Chef Lemieux if he’d

care to join us?”

With the kitchen door so close, Peter thought,

it was a temptation to stride through and inquire directly what had gone so

amiss with the luncheon special. But to do so would be unwise.

In dealing with their senior chefs, hotel

executives followed a protocol as proscribed and traditional as that of any

royal household. Within the kitchen the chef de cuisine—or, in the chef’s

absence, the sous-chef—was undisputed king. For a hotel manager to enter the

kitchen without invitation was unthinkable.

Chefs might be fired, and sometimes were. But

unless and until that happened, their kingdoms were inviolate.

To invite a chef outside the kitchen—in this

case to a table in the dining room—was in order. In fact, it was close to a

command since, in Warren Trent’s absence, Peter McDermott was the hotel’s

senior officer. It would also have been permissible for Peter to stand in the

kitchen doorway and wait to be asked in. But in the circumstance—with an

obvious crisis in the kitchen—Peter knew that the first course was the more

correct.

“If you ask me,” Sam Jakubiec observed as they

waited, “it’s long past bedtime for old Chef Hèbrand.”

Royall Edwards asked, “If he did retire, would

anyone notice the difference?” It was a reference, as they all knew, to the

chef de cuisine’s frequent absences from duty, another of which had apparently

occurred today.

“The end comes soon enough for all of us,” the

chief engineer growled. “It’s natural nae one wants to hurry it himsel’.” It

was no great secret that the comptroller’s cool astringency grated at times on

the normally good-natured chief.

“I haven’t met our new sous-chef,” Jakubiec

said. “I guess he’s been keeping his nose in the kitchen.”

As the comptroller spoke, the kitchen door

swung open once more. A busboy, about to pass through, stood back deferentially

as Max the head waiter emerged. He preceded, by several measured paces, a tall

slim figure in starched whites, with high chef’s hat and, beneath it, a facial

expression of abject misery.

“Gentlemen,” Peter announced to the

executives’ table, “in case you haven’t met, this is Chef André Lemieux.”

“Messieurs!” The young Frenchman halted,

spreading his hands in a gesture of helplessness. “To ’ave this happen … I am

desolate.” His voice was choked.

Peter McDermott had encountered the new

sous-chef several times since the latter’s arrival at the St. Gregory six weeks

earlier. At each meeting Peter found himself liking the newcomer more.

André Lemieux’s appointment had followed the

abrupt departure of his predecessor. The former sous-chef, after months of

frustrations and inward seething, had erupted in an angry outburst against his

superior, the aging M. Hebrand. In the ordinary way nothing might have happened

after the scene, since emotional outbursts among chefs and cooks occurred—as in

any large kitchen—with predictable frequency. What marked the occasion as

different was the late sous-chef’s action in hurling a tureen of soup at the

chef de cuisine. Fortunately the soup was Vichyssoise, or consequences might

have been even more serious. In a memorable scene the chef de cuisine, shrouded

in liquid white and dripping messily, escorted his late assistant to the street

staff door and there—with surprising energy for an old man—had thrown him

through it. A week later Andre Lemieux was hired.

His qualifications were excellent. He had

trained in Paris, worked in London—at Prunier’s and the Savoy—then briefly at

New York’s Le Pavilion before attaining the more senior post in New Orleans.

But already in his short time at the St. Gregory, Peter suspected, the young

sous-chef had encountered the same frustration which demented his predecessor.

This was the adamant refusal of M. Hebrand to allow procedural changes in the

kitchen, despite the chef de cuisine’s own frequent absences from duty, leaving

his sous-chef in charge. In many ways, Peter thought sympathetically, the

situation paralleled his own relationship with Warren Trent.

Peter indicated a vacant seat at the

executives’ table. “Won’t you join us?”

“Thank you, monsieur.” The young Frenchman

seated himself gravely as the head waiter held out a chair.

His arrival was followed by the table waiter

who, without bothering with instructions, had amended all four luncheon orders

to Veal Scallopini. He removed the two offending portions of chicken, which a

hovering busboy banished hastily to the kitchen. All four executives received

the substitute meal, the sous-chef ordering merely a black coffee.

“That’s more like it,” Sam Jakubiec said

approvingly.

“Have you discovered,” Peter asked, “what

caused the trouble?”

The sous-chef glanced unhappily toward the

kitchen. “The troubles they have many causes. In this, the fault was frying fat

badly tasting. But it is I who must blame myself—that the fat was not changed,

as I believed. And I, Andre Lemieux, I allowed such food to leave the kitchen.”

He shook his head unbelievingly.

“It’s hard for one person to be everywhere,”

the chief engineer said. “All of us who ha’ departments know that.”

Royall Edwards voiced the thought which had

occurred first to Peter. “Unfortunately we’ll never know how many didn’t

complain about what they had, but won’t come back again.”

André Lemieux nodded glumly. He put down his

coffee cup. “Messieurs, you will excuse me. Monsieur McDermott, when you ’ave

finished, perhaps we could talk together, yes?”

Fifteen minutes later Peter entered the

kitchen through the dining-room door. André Lemieux hurried forward to meet

him.

“It is good of you to come, monsieur.”

Peter

shook his head. “I enjoy kitchens.” Looking around, he observed that the

activity of lunchtime was tapering off. A few meals were still going out, past

the two middle-aged women checkers seated primly, like suspicious

schoolmistresses, at elevated billing registers. But more dishes were coming in

from the dining room as busboys and waiters cleared tables while the assemblage

of guests thinned out. At the big dishwashing station at the rear of the

kitchen, where chrome countertops and waste containers resembled a cafeteria in

reverse, six rubber-aproned kitchen helpers worked conceitedly, barely keeping

pace with the flow of dishes arriving from the hotel’s several restaurants and

the convention floor above. As usual, Peter noticed, an extra helper was

intercepting unused butter, scraping it into a large chrome container. Later,

as happened in most commercial kitchens—though few admitted to it—the retrieved

butter would be used for cooking.

“I wished to speak with you alone, monsieur.

With others present, you understand, there are things that are hard to say.”

Peter said thoughtfully, “There’s one point

I’m not clear about. Did I understand that you gave instructions for the deep

fryer fat to be changed, but that it was not?”

“That is true.”

“Just what happened?”

The young chef’s face was troubled. “This

morning I gave the order. My nose it informed me the fat is not good. But M.

Hebrand—without telling—he countermanded. Then M. Hélbrand he has gone ’ome and

I am left, without knowing, ’olding the bad fat.”

Involuntarily Peter smiled. “What was the

reason for changing the order?”

“Fat is high cost—very ’igh; that I agree with

M. Hébrand. Lately we have changed it many times. Too many.”

“Have you tried to find the reason for that?”

André Lemieux raised his hands in a despairing

gesture. “I have proposed, each day, a chemical test—for free fatty acid. It

could be done in a laboratory, even here. Then, intelligently, we would look

for the cause the fat has failed. M. Hébrand does not agree—with that or other

things.”

“You believe there’s a good deal wrong here?”

“Many things.” It was a short, almost sullen

answer, and for a moment it appeared as if the discussion would end. Then

abruptly, as if a dam had burst, words tumbled out. “Monsieur McDermott, I tell

you there is much wrong. This is not a kitchen to work with pride. It is a

how-you-say …’odge-podge—poor food, some old ways that are bad, some new ways

that are bad, and all around much waste. I am a good chef; others would tell

you. But it must be that a good chef is happy at what he does or he is no

longer good. Yes, monsieur, I would make changes, many changes, better for the

hotel, for M. Hébrand, for others. But I am told—as if an infant—to change

nothing.”

“It’s possible,” Peter said, “there may be

large changes around here generally. Quite soon.”

André Lemieux drew himself up haughtily. “If

you refer to Monsieur O’Keefe, whatever changes he may make, I shall not be

‘ere to see. I have no intent to be an instant cook for a chain ’otel.”

Peter asked curiously, “If the St. Gregory

stayed independent, what kind of changes would you have in mind?”

They had strolled almost the length of the

kitchen—an elongated rectangle extending the entire width of the hotel. At each

side of the rectangle, like outlets from a control center, doorways gave access

to the several hotel restaurants, service elevators and food preparation rooms

on the same floor and below. Skirting a double line of soup cauldrons, bubbling

like monstrous crucibles, they approached the glass-paneled office where, in

theory, the two principal chefs-the chef de cuisine and the sous-chef—divided

their responsibilities. Nearby, Peter observed, was the big quadruple-unit deep

fryer, cause of today’s dissatisfaction. A kitchen helper was draining the

entire assembly of fat; considering the quantity, it was easy to see why too

frequent replacement would be costly. They stopped as Andre Lemieux considered

Peter’s question.

“What changes, you say, monsieur? Most

important it is the food. For some who prepare food, the façade, how a dish

looks, it is more important than how it tastes. In this hotel we waste much

money on the decor. The parsley, it is all around. But not enough in the sauce.

The watercress it is on the plate, when more is needed in the soup. And those

arrangements of color in gelatine!” Young Lemieux threw both arms upward in

despair. Peter smiled sympathetically.

“As for the wines, monsieur! Dieu merci, the

wines they are not my province.”

“Yes,” Peter said. He had been critical

himself of the St. Gregory’s inadequately stocked wine bins.

“In a word, monsieur, all the horrors of a low-grade

table d’hôte. Such disrespect colossal for food, such abandon of money for the

appearance, it is to make one weep. Weep, monsieur!” He paused, shrugged, and

continued. “With less throw-away we could have a cuisine that invites the taste

and honors the palate. Now it is dull, extravagantly ordinary.”

Peter wondered if André Lemieux was being

sufficiently realistic where the St. Gregory was concerned. As if sensing this

doubt, the sous-chef insisted, “It is true that a hotel it has special

problems. Here it is not a gourmet house. It cannot be. We must cook fast many

meals, serve many people who are too much in an American hurry. But in these

limitations there can be excellence of a kind. Of a kind one can live with.

Yet, Monsieur Hébrand, he tells me that my ideas they are too ’igh cost. It is

not so, as I ’ave proved.”

“How have you proved?”

“Come, please.”

The young Frenchman led the way into the

glass-paneled office. It was a small, crowded cubicle with two desks, file

cabinets, and cupboards tightly packed around three walls. André Lemieux went

to the smaller desk. Opening a drawer he took out a large Manila envelope and,

from this, a folder. He handed it to Peter. “You ask what changes. It is all

here.”

Peter McDermott opened the folder curiously. There

were many pages, each filled with a fine, precise handwriting. Several larger,

folded sheets proved to be charts, hand-drawn and lettered in the same careful

style. It was, he realized, a master catering plan for the entire hotel. On

successive pages were estimated costs, menus, a plan of quality control and an

outlined staff reorganization. Merely leafing through quickly, the entire

concept and its author’s grasp of detail were impressive.

Peter looked up, catching his companion’s eyes

upon him. “If I may, I’d like to study this.”

‘Take it. There is no haste.” The young

sous-chef smiled dourly. “I am told it is unlikely any of my ’orses will come

’ome.”

“The thing that surprises me is how you could

develop something like this so quickly.”

André Lemieux shrugged. “To perceive what is

wrong, it does not take long.”

“Maybe we could apply the same idea in finding

what went wrong with the deep fryer.”

There was a responsive gleam of humor, then

chagrin. “Touché! It is true—I had eyes for this, but not the ’ot fat under my

nose.”

“No,” Peter objected. “From what you’ve told

me, you did detect the bad fat but it wasn’t changed as you instructed.”

“I should have found the cause the fat went

bad. There is always a cause. Greater trouble there may be if we do not find it

soon.”

“What kind of trouble?”

“Today—through much good fortune—we have used

the frying fat a little only. Tomorrow, monsieur, there are six hundred fryings

for convention luncheons.”

Peter

whistled softly.

“Just

so.” They had walked together from the office to stand beside the deep fryer

from which the last vestiges of the recently offending fat were being cleaned.

“The

fat will be fresh tomorrow, of course. When was it changed previously?”

“Yesterday.”

“That

recently!”

André

Lemieux nodded. “M. Hèbrand he was making no joke when he complained of the

’igh cost. But what is wrong it is a mystery.”

Peter

said slowly, “I’m trying to remember some bits of food chemistry. The

smoke-point of new, good fat is …”

“Four

’undred and twenty-five degrees. It should never be heated more, or it will

break down.”

“And as

fat deteriorates its smoke-point drops slowly.”

“Very

slowly—if all is well.”

“Here

you fry at …”

“Three

’undred and sixty degrees; the best temperature—for kitchens and the ’ousewives

too.”

“So while

the smoke-point remains about three hundred and sixty, the fat will do its job.

Below that, it ceases to.”

“That is true, monsieur. And the fat it will

give food a bad flavor, tasting rancid, as today.”

Facts, once memorized but rusty with disuse,

stirred in Peter’s brain. At Cornell there had been a course in food chemistry

for Hotel Administration students. He remembered a lecture dimly … in Statler

Hall on a darkening afternoon, the whiteness of frost on window panes. He had

come in from the biting, wintry air outside. Inside was warmth and the drone of

information …fats and catalyzing agents.

“There

are certain substances,” Peter said reminiscently, “which, in contact with fat,

will act as catalysts and break it down quite quickly.”

“Yes,

monsieur.” Andre Lemieux checked them off on his fingers. “They are the

moisture, the salt, the brass or the copper couplings in a fryer, too much

’eat, the oil of the olive. All these things I have checked. This is not the

cause.”

A word

had clicked in Peter’s brain. It connected with what he had observed,

subconsciously, in watching the deep fryer being cleaned a moment earlier.

“What

metal are your fry baskets?”

“They

are chrome.” The tone was puzzled. Chromium, as both men knew, was harmless to

fat.

“I

wonder,” Peter said, “how good the plating job is. If it isn’t good, what’s

under the chrome and is it—in any places—worn?”

Lemieux

hesitated, his eyes widening slightly. Silently he lifted one of the baskets

down and wiped it carefully with a cloth. Moving under a light, they inspected

the metal surface.

The

chrome was scratched from long and constant use. In small spots it had worn

away entirely. Beneath scratches and worn spots was a gleam of yellow.

“It is

brass!” The young Frenchman clapped a hand to his forehead. “Without doubt it

’as caused the bad fat. I have been a great fool.”

“I don’t see how you can blame yourself,”

Peter pointed out. “Obviously, long before you came, someone economized and

bought cheap fry baskets. Unfortunately it’s cost more in the end.”

“But I should have discovered this—as you have

done, monsieur.” Andre Lemieux seemed close to tears. “Instead, you, monsieur,

you come to the kitchen—from your paper-asserie—to tell me what is ’aywire

here. It will be a laughing joke.”

“If it is,” Peter said, “it will be because

you talked about it yourself. No one will hear from me.”

André Lemieux said slowly, “Others they have

said to me you are a good man, and intelligent. Now, myself, I know this is

true.”

Peter touched the folder in his hand. “I’ll

read your report and tell you what I think.”

“Thank you, monsieur. And I shall demand new

fry baskets. Of stainless steel. Tonight they will be here if I have to ’ammer

someone’s ’ead.”

Peter smiled.

“Monsieur, there is something else that I am

thinking.”

“Yes?”

The young sous-chef hesitated. “You will think

it, how you say, presumptuous. But you and I, Monsieur McDermott—with the hands

free—we could make this a ’otshot hotel.”

Though he laughed impulsively, it was a

statement which Peter McDermott thought about all the way to his office on the

main mezzanine.

4. října 2020

Elementary... nebo ne?

1. TRUST NO ONE - not even yourself.

Adaptovaný citát ze seriálu X-files je v překladatelském životě nejčastější aplikovanou poučkou. Aneb - ověřovat. Jeden zdroj nikdy nestačí. A když máte pocit, že je všechno naprosto jasné a jednoduché, je čas zapochybovat a ověřovat.

2. YOUR RESPONSIBILITY.

Bez ohledu na množství zdrojů je za výsledný překlad zodpovědný jediný člověk - vy. Překladatel. Pravopis, interpunkce, opravené překlepy, formátování, věcná správnost, reálie, idiomy... To vše je jen a jen vaše zodpovědnost. V branži, kde je přirozeně vysoká konkurence, můžete dobrou pověst ztratit jen jednou.

__________________________

Pečlivě si přečtěte následující text a ujistěte se, že mu perfektně rozumíte. Co vše to obnáší?

Přeložte tučně vyznačenou část. Překlad vložte do komentáře k tomuto blogu do neděle 11.10.2020 12h.

J.K.ROWLING - HARRY POTTER AND THE DEATHLY HALLOWS

“It’s not over yet,” said Harry, and he raised his voice and called, “Kreacher!”

There was a loud crack and the house elf that Harry had so reluctantly inherited from Sirius appeared out of nowhere in front of the cold and empty fireplace: tiny, half human-sized, his pale skin hanging off him in folds, white hair sprouting copiously from his batlike ears. He was still wearing the filthy rag in which they had first met him, and the contemptuous look he bent upon Harry showed that his attitude to his change of ownership had altered no more than his outfit.

“Master,” croaked Kreacher in his bullfrog’s voice, and he bowed low; muttering to his knees, “back in my Mistress’s old house with the blood-traitor Weasley and the Mudblood—“

“I forbid you to call anyone ’blood traitor’ or ’Mudblood,”’ growled Harry. He would have found Kreacher, with his snoutlike nose and bloodshot eyes, a distinctively unlovable object even if the elf had not betrayed Sirius to Voldemort.

“I’ve got a question for you,” said Harry, his heart beating rather fast as he looked down at the elf, “and I order you to answer it truthfully. Understand?”

“Yes, Master,” said Kreacher, bowing low again. Harry saw his lips moving soundlessly, undoubtedly framing the insults he was now forbidden to utter.

“Two years ago,” said Harry, his heart now hammering against his ribs, “there was a big gold locket in the drawing room upstairs. We threw it out. Did you steal it back?”

There was a moment’s silence, during which Kreacher straightened up to look Harry full in the face. Then he said, “Yes.”

“Where is it now?” asked Harry jubilantly as Ron and Hermione looked gleeful. Kreacher closed his eyes as though he could not bear to see their reactions to his next word.

“Gone.”

“Gone?” echoed Harry, elation floating out of him, “What do you mean, it’s gone?”

The elf shivered. He swayed.

“Kreacher,” said Harry fiercely, “I order you—“

“Mundungus Fletcher,” croaked the elf, his eyes still tight shut. “Mundungus Fletcher stole it all; Miss Bella’s and Miss Cissy’s pictures, my Mistress’s gloves, the Order of Merlin, First Class, the goblets with the family crest, and— and—“

Kreacher was gulping for air: His hollow chest was rising and falling rapidly, then his eyes flew open and he uttered a bloodcurdling scream.

“—and the locket, Master Regulus’s locket. Kreacher did wrong, Kreacher failed in his orders!”

Harry reacted instinctively: As Kreacher lunged for the poker standing in the grate, he launched himself upon the elf, flattening him. Hermione’s scream mingled with Kreacher’s but Harry bellowed louder than both of them:

“Kreacher, I order you to stay still!”

He felt the elf freeze and released him. Kreacher lay flat on the cold stone floor, tears gushing from his sagging eyes.

“Harry, let him up!” Hermione whispered.

“So he can beat himself up with the poker?” snorted Harry, kneeling beside the elf. “I don’t think so. Right. Kreacher, I want the truth: How do you know Mundungus Fletcher stole the locket?”

“Kreacher saw him!” gasped the elf as tears poured over his snout and into his mouth full of graying teeth. “Kreacher saw him coming out of Kreacher’s cupboard with his hands full of Kreacher’s treasures. Kreacher told the sneak thief to stop, but Mundungus Fletcher laughed and r-ran. . . . “

“You called the locket ’Master Regulus’s,”’ said Harry. “Why? Where did it come from? What did Regulus have to do with it? Kreacher, sit up and tell me everything you know about that locket, and everything Regulus had to do with it!”

The elf sat up, curled into a ball, placed his wet face between his knees, and began to rock backward and forward. When he spoke, his voice was muffled but quite distinct in the silent, echoing kitchen. “Master Sirius ran away, good riddance, for he was a bad boy and broke my Mistress’s heart with his lawless ways. But Master Regulus had proper order; he knew what was due to the name of Black and the dignity of his pure blood. For years he talked of the Dark Lord, who was going to bring the wizards out of hiding to rule the Muggles and the Muggle-borns . . . and when he was sixteen years old, Master Regulus joined the Dark Lord. So proud, so proud, so happy to serve . . .

17. dubna 2020

Finale - Bukowski

Máte před sebou poslední letošní zadání :) Pečlivě a v klidu si přečtěte celou povídku. Pár dní o ní přemýšlejte. Pak čtěte znovu, tentokrát už z hlediska překladatele. Které prvky tu tvoří tvoří autorský styl? Které věty nesou pointu?

Můžete, ale nemusíte přeložit povídku celou. Požadované minimum je jedna normostrana - 1800 znaků. Vyberte si úsek, který dává smysl a nekončí v půli věty či odstavce!

Můžete se také domluvit ve skupinkách o 2-4 členech a společně pořídít překlad celé povídky.

Deadline - 7.5.2020

_______