6. února 2019

Dobrodružství v divočině

Jack London

LOVE OF LIFE

"This out of all will remain--

They have lived and have tossed:

So much of the game will be gain,

Though the gold of the dice has been lost."

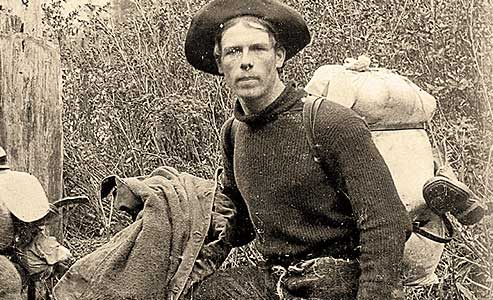

They limped painfully down the bank, and once the foremost of the two men

staggered among the rough-strewn rocks. They were tired and weak, and

their faces had the drawn expression of patience which comes of hardship

long endured. They were heavily burdened with blanket packs which were

strapped to their shoulders. Head-straps, passing across the forehead,

helped support these packs. Each man carried a rifle. They walked in a

stooped posture, the shoulders well forward, the head still farther

forward, the eyes bent upon the ground.

"I wish we had just about two of them cartridges that's layin' in that

cache of ourn," said the second man.

His voice was utterly and drearily expressionless. He spoke without

enthusiasm; and the first man, limping into the milky stream that foamed

over the rocks, vouchsafed no reply.

The other man followed at his heels. They did not remove their

foot-gear, though the water was icy cold--so cold that their ankles ached

and their feet went numb. In places the water dashed against their

knees, and both men staggered for footing.

The man who followed slipped on a smooth boulder, nearly fell, but

recovered himself with a violent effort, at the same time uttering a

sharp exclamation of pain. He seemed faint and dizzy and put out his

free hand while he reeled, as though seeking support against the air.

When he had steadied himself he stepped forward, but reeled again and

nearly fell. Then he stood still and looked at the other man, who had

never turned his head.

The man stood still for fully a minute, as though debating with himself.

Then he called out:

"I say, Bill, I've sprained my ankle."

Bill staggered on through the milky water. He did not look around. The

man watched him go, and though his face was expressionless as ever, his

eyes were like the eyes of a wounded deer.

The other man limped up the farther bank and continued straight on

without looking back. The man in the stream watched him. His lips

trembled a little, so that the rough thatch of brown hair which covered

them was visibly agitated. His tongue even strayed out to moisten them.

"Bill!" he cried out.

It was the pleading cry of a strong man in distress, but Bill's head did

not turn. The man watched him go, limping grotesquely and lurching

forward with stammering gait up the slow slope toward the soft sky-line

of the low-lying hill. He watched him go till he passed over the crest

and disappeared. Then he turned his gaze and slowly took in the circle

of the world that remained to him now that Bill was gone.

Near the horizon the sun was smouldering dimly, almost obscured by

formless mists and vapors, which gave an impression of mass and density

without outline or tangibility. The man pulled out his watch, the while

resting his weight on one leg. It was four o'clock, and as the season

was near the last of July or first of August,--he did not know the

precise date within a week or two,--he knew that the sun roughly marked

the northwest. He looked to the south and knew that somewhere beyond

those bleak hills lay the Great Bear Lake; also, he knew that in that

direction the Arctic Circle cut its forbidding way across the Canadian

Barrens. This stream in which he stood was a feeder to the Coppermine

River, which in turn flowed north and emptied into Coronation Gulf and

the Arctic Ocean. He had never been there, but he had seen it, once, on

a Hudson Bay Company chart.

Again his gaze completed the circle of the world about him. It was not a

heartening spectacle. Everywhere was soft sky-line. The hills were all

low-lying. There were no trees, no shrubs, no grasses--naught but a

tremendous and terrible desolation that sent fear swiftly dawning into

his eyes.

"Bill!" he whispered, once and twice; "Bill!"

He cowered in the midst of the milky water, as though the vastness were

pressing in upon him with overwhelming force, brutally crushing him with

its complacent awfulness. He began to shake as with an ague-fit, till

the gun fell from his hand with a splash. This served to rouse him. He

fought with his fear and pulled himself together, groping in the water

and recovering the weapon. He hitched his pack farther over on his left

shoulder, so as to take a portion of its weight from off the injured

ankle. Then he proceeded, slowly and carefully, wincing with pain, to

the bank.

Přihlásit se k odběru:

Komentáře (Atom)