Casablanca - the movie: Marseillaise: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTsg9i6lvqU

4. prosince 2017

27. listopadu 2017

18. listopadu 2017

Námořnictvo, symbol Británie

Říká se, že každý Brit je v jádru námořník. Těžko soudit - nicméně námořní tématika se v anglicky psané literatuře objevuje velice často, a beletrie si precizností vyjadřování nezadá s odbornou literaturou.

Kniha Alistaira MacLeana H.M.S. Ulyssess vyšla poprvé v roce 1955 a byla dokonce zfilmována. Děj se na základě vlastních zkušeností autora zabývá osudy příslušníků Královského námořnictva za druhé světové války.

1. Zjistěte si více o autorovi a díle, přečtěte si synapsi. Kompletní originál v pdf je k dispozici na capse.

2. Z první části textu vyberte technické termíny a vyhledejte jejich význam.

3. Přeložte druhou (vyznačenou) část textu.

Jak si s podobným textem poradili vaši předchůdci - LINK

________________

Corvette

Frigate

Squadron

Cargo liner

Destroyer

long fo'c'sle deck

square cruiser stern

Asdic

Wardroom

Parsons single-reduction geared turbines

twin gun-turrets, two for'ard, two aft,

AA, the batteries of multiple pom-poms

twin Oerlikons

depth-charges

Kniha Alistaira MacLeana H.M.S. Ulyssess vyšla poprvé v roce 1955 a byla dokonce zfilmována. Děj se na základě vlastních zkušeností autora zabývá osudy příslušníků Královského námořnictva za druhé světové války.

1. Zjistěte si více o autorovi a díle, přečtěte si synapsi. Kompletní originál v pdf je k dispozici na capse.

2. Z první části textu vyberte technické termíny a vyhledejte jejich význam.

3. Přeložte druhou (vyznačenou) část textu.

Jak si s podobným textem poradili vaši předchůdci - LINK

________________

A

ghost-ship, almost, a legend. The Ulysses was also a young ship, but she had

grown old in the Russian Convoys H.U.33B and on the Arctic patrols. She had

been there from the beginning, and had known no other life. At first she had

operated alone, escorting single ships or groups of two or three: later, she

had operated with corvettes and frigates, and now she never moved without her

squadron, the 14th Escort Carrier group.

But

the Ulysses had never really sailed alone. Death had been, still was, her

constant companion. He laid his ringer on a tanker, and there was the erupting

hell of a high-octane detonation; on a cargo liner, and she went to the bottom

with her load of war supplies, her back broken by a German torpedo; on a

destroyer, and she knifed her way into the grey-black depths of the Barents

Sea, her still racing engines her own executioners; on a U-boat, and she

surfaced violently to be destroyed by gunfire, or slid down gently to the

bottom of the sea, the dazed, shocked crew hoping for a cracked pressure hull

and merciful instant extinction, dreading the endless gasping agony of

suffocation in their iron tomb on the ocean floor. Where the Ulysses went,

there also went death. But death never touched her. She was a lucky ship. A

lucky ship and a ghost ship and the Arctic was her home.

Illusion,

of course, this ghostliness, but a calculated illusion. The Ulysses was

designed specifically for one task, for one ocean, and the camouflage experts

had done a marvellous job. The special Arctic camouflage, the broken, slanting

diagonals of grey and white and washed out blues merged beautifully, imperceptibly

into the infinite shades of grey and white, the cold, bleak grimness of the

barren northern seas.And the camouflage was only the outward, the superficial

indication of her fitness for the north.

Technically, the Ulysses was a light cruiser. She was the

only one of her kind, a 5,500 ton modification of the famous Dido type, a

forerunner of the Black Prince class. Five hundred and ten feet long, narrow in

her fifty-foot beam with a raked stem, square cruiser stern and long fo'c'sle

deck extending well abaft the bridge, a distance of over two hundred feet, she

looked and was a lean, fast and compact warship, dangerous and durable. "Locate:

engage: destroy." These are the classic requirements of a naval ship in

wartime, and to do each, and to do it with maximum speed and efficiency, the

Ulysses was superbly equipped. Location, for instance. The human element, of

course, was indispensable, and Vallery was far too experienced and battlewise a

captain to underestimate the value of the unceasing vigil of look-outs and signalmen.

The human eye was not subject to blackouts, technical hitches or mechanical

breakdowns. Radio reports, too, had their place and Asdic, of course, was the

only defence against submarines.

But

the Ulysses's greatest strength in location lay elsewhere. She was the first

completely equipped radar ship in the world. Night and day, the radar scanners

atop the fore and main tripod masts swept ceaselessly in a 360° arc, combing

the far horizons, searching, searching. Below, in the radar rooms, eight in

all, and in the Fighter Direction rooms, trained eyes, alive to the slightest

abnormality, never left the glowing screens. The radar's efficiency and range

were alike fantastic. The makers, optimistically, as they had thought, had

claimed a 40-45 mile operating range for their equipment. On the Ulysses's

first trials after her refit for its installation, the radar had located a

Condor, subsequently destroyed by a Blenheim, at a

range

of eighty-five miles.

Engage

that was the next step. Sometimes the enemy came to you, more often you had to

go after him. And then, one thing alone mattered speed. The Ulysses was

tremendously fast. Quadruple screws powered by four great Parsons

single-reduction geared turbines two in the for'ard, two in the after

engine-room, developed an unbelievable horse-power that many a battleship, by

no means obsolete, could not match. Officially, she was rated at 33.5 knots.

Off Arraa, in her full-power trials, bows lifting out of the water, stern dug

in like a hydroplane, vibrating in every Clyde-built rivet, and with the

tortured, seething water boiling whitely ten feet above the level of the

poop-deck, she had covered the measured mile at an incredible 39.2 knots, the

nautical equivalent of 45 m.p.h. And the "Dude "-Engineer-Commander

Dobson had smiled knowingly, said he wasn't half trying and just wait till the

Abdiel or the Manxman came along, and he'd show them something. But as these famous

mine-laying cruisers were widely believed to be capable of 44 knots, the

wardroom had merely sniffed "Professional jealousy "and ignored him. Secretly,

they were as proud of the great engines as Dobson himself.

Locate,

engage and destroy. Destruction. That was the be all, the end all. Lay the

enemy along the sights and destroy him. The Ulysses was well equipped for that

also. She had four twin gun-turrets, two for'ard, two aft, 5.25 quick-firing

and dual-purpose equally effective against surface targets and aircraft. These

were controlled from the Director Towers, the main one for'ard, just above and

abaft of the bridge, the auxiliary aft. From these towers, all essential data about

bearing, wind-speed, drift, range, own speed, enemy speed, respective angles of

course were fed to the giant electronic computing tables in the Transmitting

Station, the fighting heart of the ship, situated, curiously enough, in the

very bowels of the Ulysses, deep below the water-line, and thence automatically

to the turrets as two simple factors, elevation and training. The turrets, of

course, could also fight independently.

These

were the main armament. The remaining guns were purely AA, the batteries of

multiple pom-poms, firing two-pounders in rapid succession, not particularly

accurate but producing a blanket curtain sufficient to daunt any enemy pilot,

and isolated clusters of twin Oerlikons, high-precision, high-velocity weapons,

vicious and deadly in trained hands.

Finally,

the Ulysses carried her depth-charges and torpedoes, 36 charges only, a

negligible number compared to that carried by many corvettes and destroyers,

and the maximum number that could be dropped in one pattern was six. But one depth-charge

carries 450 lethal pounds of Amatol, and the Ulysses had destroyed two U-boats

during the preceding winter. The 21-inch torpedoes, each with its 750-pound

warhead of T.N.T., lay sleek and menacing, in the triple tubes on the main

deck, one set on either side of the after funnel. These had not yet been

blooded.

This,

then, was the Ulysses. The complete, the perfect fighting machine, man's

ultimate, so far, in his attempt to weld science and savagery into an

instrument of destruction. The perfect fighting machine, but only so long as it

was manned and serviced by a perfectly integrating, smoothly functioning team.

A ship, any ship, can never be better than its crew. And the crew of the

Ulysses was disintegrating, breaking up: the lid was clamped on the volcano,

but the rumblings never ceased.

Corvette

Frigate

Squadron

Cargo liner

Destroyer

long fo'c'sle deck

square cruiser stern

Asdic

Wardroom

Parsons single-reduction geared turbines

twin gun-turrets, two for'ard, two aft,

AA, the batteries of multiple pom-poms

twin Oerlikons

depth-charges

Then

it happened. It was A.B. Ferry's fault that it happened. And it was just

ill-luck that the port winch was suspect, operating on a power circuit with a

defective breaker, just ill-luck that Ralston was the winch driver, a taciturn,

bitter mouthed Ralston to whom, just then, nothing mattered a damn, least of

all what he said and did. But it was Carslake's responsibility that the affair

developed into what it did.

Sub-Lieutenant

Carslake's presence there, on top of the Carley floats', directing the handling

of the port wire, represented the culmination of a series of mistakes. A

mistake on the part of his father, Rear- Admiral, Rtd., who had seen in his son

a man of his own calibre, had dragged him out of Cambridge in 1939 at the

advanced age of twenty-six and practically forced him into the Navy: a weakness

on the part of his first C.O., a corvette captain who had known his father and

recommended him as a candidate for a commission: a rare error of judgment on

the part of the selection board of the King Alfred, who had granted him his

commission ; and a temporary lapse on the part of the Commander, who had

assigned him to this duty, in spite of Carslake's known incompetence and

inability to handle men.

He had

the face of an overbred racehorse, long, lean and narrow, with prominent pale

blue eyes and protruding upper teeth. Below his scanty fair hair, his eyebrows

were arched in a perpetual question mark: beneath the long, pointed nose, the

supercilious curl of the upper lip formed the perfect complement to the eyebrows.

His speech was a shocking caricature of the King's English: his short vowels

were long, his long ones interminable: his grammar was frequently execrable. He

resented the Navy, he resented his long overdue promotion to Lieutenant, he

resented the way the men resented him. In brief, Sub-Lieutenant Carslake was

the quintessence of the worst by-product of the English public school system.

Vain, superior, uncouth and ill-educated, he was a complete ass.

He was

making an ass of himself now. Striving to maintain balance on the rafts, feet

dramatically braced at a wide angle, he shouted unceasing, unnecessary commands

at his men. C.P.O. Hartley groaned aloud, but kept otherwise silent in the

interests of discipline. But A.B. Ferry felt himself under no such restraints. "'Ark

at his Lordship," he murmured to Ralston. "All for the Skipper's

benefit." He nodded at where Vallery was leaning over the bridge, twenty

feet above Carslake's head. "Impresses him no end, so his nibs

reckons."

"Just

you forget about Carslake and keep your eyes on that wire,"

Ralston

advised. "And take these damned great gloves off. One of these

days------"

"Yes,

yes, I know," Ferry jeered. "The wire's going to snag 'em and wrap me

round the drum." He fed in the hawser expertly. "Don't you worry,

chum, it's never going to happen to me."

But it

did. It happened just then. Ralston, watching the swinging paravane closely,

flicked a glance inboard. He saw the broken strand inches from Ferry, saw it

hook viciously into the gloved hand and drag him towards the spinning drum

before Ferry had a chance to cry out.

Ralston's

reaction was immediate. The foot-brake was only six inches away but that was

too far. Savagely he spun the control wheel, full ahead to full reverse in a

split second. Simultaneously with Ferry's cry of pain as his forearm crushed

against the lip of the drum came a muffled explosion and clouds of acrid smoke

from the winch as £500 worth of electric motor burnt out in a searing flash. Immediately

the wire began to run out again, accelerating momentarily under the dead weight

of the plunging paravane. Ferry went with it. Twenty feet from the winch the

wire passed through a snatch block on the deck: if Ferry was lucky, he might

lose only his hand.

He was

less than four feet away when Ralston's foot stamped viciously on the brake.

The racing drum screamed to a shuddering stop, the paravane crashed down into

the sea and the wire, weightless now, swung idly to the rolling of the ship.

Carslake

scrambled down off the Carley, his sallow face suffused with anger. He strode

up to Ralston.

"You

bloody fool!" he mouthed furiously. "You've lost us that paravane.

By

God, L.T.O., you'd better explain yourself! Who the hell gave you orders to do

anything?"

Ralston's

mouth tightened, but he spoke civilly enough.

"Sorry,

sir. Couldn't help it, it had to be done. Ferry's arm------"

"To

hell with Ferry's arm!" Carslake was almost screaming with rage.

"I'm

in charge here and I give the orders. Look! Look!" He pointed to the

swinging wire. "Your work, Ralston, you, you blundering idiot! It's gone,

gone, do you understand, gone!"

Ralston

looked over the side with an air of large surprise.

"Well,

now, so it is." The eyes were bleak, the tone provocative, as he looked

back at Carslake and patted the winch. "And don't forget this, it's gone

too, and it costs a ruddy sight more than any paravane."

"I

don't want any of your damned impertinence!" Carslake shouted. His mouth

was working, his voice shaking with passion. "What you need is to have

some discipline knocked into you and, by God, I'm going to see you get it, you

insolent young bastard!"

Ralston

flushed darkly. He took one quick step forward, his fist balled, then relaxed

heavily as the powerful hands of C.P.O. Hartley caught his swinging arm. But

the damage was done now. There was nothing for it but the bridge.

13. listopadu 2017

Hudba a text

HW: registrujte si povídku k finálnímu překladu! Na capse jsou k dispozici soubory z díla E. Hemingwaye a R. Bradburyho.

Poválečná populární hudba, to bylo v padesátých a šedesátých letech především zázračné "rádio Laxemberg," z něhož později čerpaly stále četnější české adaptace americké hudby. Ovšem "poklesle kapitalistický" anglický text byl v pokrokovém socialistickém státě nepřijatelný a nepřípustný! Od šedesátých let 20. století se tak intenzivně rozvíjela česká překladová textařina, a často bojovala s nesmyslnou cenzurou. V textu se například nesmělo objevit slova bible nebo Ježíš - tak vznikla záhadná řádka z textu skupiny Spirituál kvintet "Ten starý příběh z knížky vám tu vykládám", nebo název písně "Jesus met a woman" - v české verzi Poutník a dívka.

V současnosti má většina světových písní pop music anglické texty, bez ohledu na národnost autorů a interpretů. Ani ty, které posloucháme česky, nemusejí pocházet z domácí produkce - často čeští interpreti převezmou světový hit a dodají mu český text. Byznys je byznys!

Česká tradice písňových překladů sahá hluboko do historie.

Divotvorný hrnec

U nás doma (How Are Things In Glocca Morra): Burton Lane, V+W

Zpívá Soňa Červená, mluví Václav Trégl

Karel Vlach se svým orchestrem

ULTRAPHON C 15130, mat. 45770, rec. PRAHA 23.4.1948

Americký muzikál Finian's Rainbow (Divotvorný hrnec) napsal Burton Lane na text E. Y. Harburga. Hudbu přepsal z původních gramofonových desek natočených v roce 1947 v New Yorku Zdeněk Petr, který hudbu i aranžoval. Pražské provedení bylo první v Evropě.

Ukázka ze slavné filmové verze

BEGAT in English

Množení - Werich

1. Znáte nějaké české verze původně anglických písní? Uveďte příklady v komentáři k blogu!

2. A jak se přeložené dílko proměňuje? Porovnejte:

Red river

Červená řeka

Three Ravens - A. Scholl

Three Ravens - Djazia

Three Ravens - vocal

Válka růží

L'important C'est la rose

Podívej, kvete růže

Všimněte si, jak se proměnilo i hudební provedení.

Další inspirace z oblasti téměř zlidovělé české popové klasiky zde - Ivo Fišer

http://www.casopisfolk.cz/Textari/textari-fischer_ivo0610.htm

I díla českých písničkářů jasně dokazují, že dobrý a vtipný text je silnou stránkou naší hudební scény.

Zuzana Navarová - Marie

Karel Kryl - Karavana mraků

Karel Plíhal - Nosorožec

Michal Tučný, Rattlesnake Annie - Long Black Limousine

My čekali jaro

... a zatím přišel mráz

Oh, dem golden slippers - parodie (info - WIKI)

Dobrodružství s bohem Panem

Greensleeves

3. Naším úkolem bude OTEXTOVAT píseň s původně anglickým textem. Nejsme nijak vázáni obsahem originálu, rozhoduje jedině forma, zpívatelnost - slovní a hudební přízvuky se musí překrývat. Zvolte si styl - a držte se ho, ať už to bude drama, lyrika nebo ostrá parodie.

Vyberte si jednu z níže uvedených tří skladeb a napište nový český text.

Soldier of Fortune - Deep Purple

Tears in Heaven - Eric Clapton

Give me Love - Ed Sheeran

4. Že nepoznáte přízvuk ani v textu, natož v hudbě?

Zkuste si polohlasně zarecitovat a označit přízvučné slabiky:

Je to chůze po tom světě -

kam se noha šine:

sotva přejdeš jedny hory,

hned se najdou jiné.

Je to život na tom světě -

že by člověk utek:

ještě nezažil jsi jeden,

máš tu druhý smutek.

A teď si poslechněte zhudebněnou verzi - přízvuky jsou v ní patrné daleko lépe:

Pocestný

Délky not a slabik také hrají svou roli:

. . - - . . - -

. . - - . .

. . - - . . - -

. . - - . .

__________________________________________________________

Amazing Grace

Gott https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYG52fKoRw0

text Zdeněk Borovec http://www.karaoketexty.cz/texty-pisni/gott-karel/uz-z-hor-zni-zvon-36571

Nedvědi https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XagCL9YyBH8

Il Divo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYMLMj-SibU

Poválečná populární hudba, to bylo v padesátých a šedesátých letech především zázračné "rádio Laxemberg," z něhož později čerpaly stále četnější české adaptace americké hudby. Ovšem "poklesle kapitalistický" anglický text byl v pokrokovém socialistickém státě nepřijatelný a nepřípustný! Od šedesátých let 20. století se tak intenzivně rozvíjela česká překladová textařina, a často bojovala s nesmyslnou cenzurou. V textu se například nesmělo objevit slova bible nebo Ježíš - tak vznikla záhadná řádka z textu skupiny Spirituál kvintet "Ten starý příběh z knížky vám tu vykládám", nebo název písně "Jesus met a woman" - v české verzi Poutník a dívka.

V současnosti má většina světových písní pop music anglické texty, bez ohledu na národnost autorů a interpretů. Ani ty, které posloucháme česky, nemusejí pocházet z domácí produkce - často čeští interpreti převezmou světový hit a dodají mu český text. Byznys je byznys!

Česká tradice písňových překladů sahá hluboko do historie.

Divotvorný hrnec

U nás doma (How Are Things In Glocca Morra): Burton Lane, V+W

Zpívá Soňa Červená, mluví Václav Trégl

Karel Vlach se svým orchestrem

ULTRAPHON C 15130, mat. 45770, rec. PRAHA 23.4.1948

Americký muzikál Finian's Rainbow (Divotvorný hrnec) napsal Burton Lane na text E. Y. Harburga. Hudbu přepsal z původních gramofonových desek natočených v roce 1947 v New Yorku Zdeněk Petr, který hudbu i aranžoval. Pražské provedení bylo první v Evropě.

Ukázka ze slavné filmové verze

BEGAT in English

Množení - Werich

1. Znáte nějaké české verze původně anglických písní? Uveďte příklady v komentáři k blogu!

2. A jak se přeložené dílko proměňuje? Porovnejte:

Red river

Červená řeka

Three Ravens - A. Scholl

Three Ravens - Djazia

Three Ravens - vocal

Válka růží

L'important C'est la rose

Podívej, kvete růže

Všimněte si, jak se proměnilo i hudební provedení.

Další inspirace z oblasti téměř zlidovělé české popové klasiky zde - Ivo Fišer

http://www.casopisfolk.cz/Textari/textari-fischer_ivo0610.htm

I díla českých písničkářů jasně dokazují, že dobrý a vtipný text je silnou stránkou naší hudební scény.

Zuzana Navarová - Marie

Karel Kryl - Karavana mraků

Karel Plíhal - Nosorožec

Michal Tučný, Rattlesnake Annie - Long Black Limousine

My čekali jaro

... a zatím přišel mráz

Oh, dem golden slippers - parodie (info - WIKI)

Dobrodružství s bohem Panem

Greensleeves

3. Naším úkolem bude OTEXTOVAT píseň s původně anglickým textem. Nejsme nijak vázáni obsahem originálu, rozhoduje jedině forma, zpívatelnost - slovní a hudební přízvuky se musí překrývat. Zvolte si styl - a držte se ho, ať už to bude drama, lyrika nebo ostrá parodie.

Vyberte si jednu z níže uvedených tří skladeb a napište nový český text.

Soldier of Fortune - Deep Purple

Tears in Heaven - Eric Clapton

Give me Love - Ed Sheeran

4. Že nepoznáte přízvuk ani v textu, natož v hudbě?

Zkuste si polohlasně zarecitovat a označit přízvučné slabiky:

Je to chůze po tom světě -

kam se noha šine:

sotva přejdeš jedny hory,

hned se najdou jiné.

Je to život na tom světě -

že by člověk utek:

ještě nezažil jsi jeden,

máš tu druhý smutek.

A teď si poslechněte zhudebněnou verzi - přízvuky jsou v ní patrné daleko lépe:

Pocestný

Délky not a slabik také hrají svou roli:

. . - - . . - -

. . - - . .

. . - - . . - -

. . - - . .

__________________________________________________________

Amazing Grace

Gott https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYG52fKoRw0

text Zdeněk Borovec http://www.karaoketexty.cz/texty-pisni/gott-karel/uz-z-hor-zni-zvon-36571

Nedvědi https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XagCL9YyBH8

Il Divo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYMLMj-SibU

30. října 2017

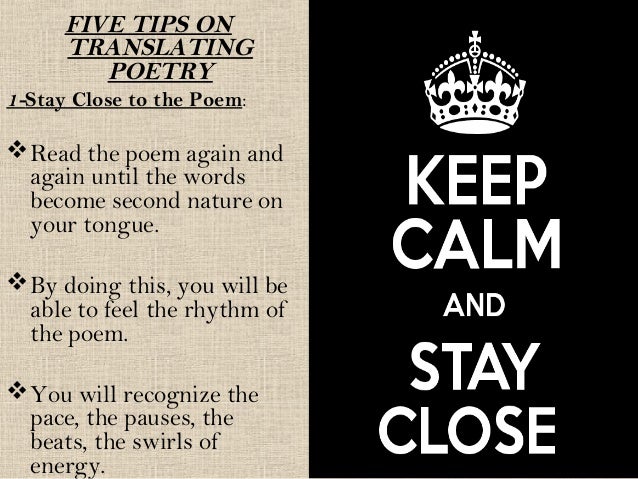

Poetry. What is poetry?

Jak překládat poezii? A překládat ji vůbec? Má přednost forma či obsah? Dají se na překlad poesie aplikovat pravidla, o kterých jsme mluvili?

1. Projděte si komentáře k předchozímu vstupu. Jaké typy básnické tvorby se objevují? Mají něco společného?

Dokážete se během 2 minut naučit 4 libovolné řádky zpaměti? Jak postupujete?

2. Stáhněte si z capsy soubor s různými verzemi překladu Shakespearova sonetu.

Shakespeare_Sonet66_13prekladu.doc

Která verze se vám nejvíc líbí? Proč? Napište svůj názor do komentáře k tomuto blogu. Uvažujete nad formou a obsahem nebo více nasloucháte svým pocitům?

Sonet 66 English

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4MWBW_c7Fsw

Sonet 66 Hilský

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SJw5BQba7zQ

__________________________________

3. Přečtěte si pomalu a klidně následující sonet. Vnímejte rytmus a zvukomalbu textu, při druhém čtení se teprve víc soustřeďte na obsah.

SONNET XII

When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silver'd o'er with white;

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves 5

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer's green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard,

Then of thy beauty do I question make,

That thou among the wastes of time must go, 10

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow;

And nothing 'gainst Time's scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him when he takes thee hence.

Pokuste se přeložit jedno ze tří čtyřverší + poslání.

Rozmyslete si, jak budete postupovat.

_______________________

originál

https://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/views/sonnets/sonnets.php

české překlady Shakespeara

Jan Vladislav-pdf

http://lukaflek.wz.cz/poems/ws_sonet29.htm

http://www.v-art.cz/taxus_bohemica/eh/bergrova.htm

http://www.shakespearovy-sonety.cz/a29/

Hilsky sonet 12 youtube

http://sonety.blog.cz/0803/william-shakespeare-sonnet-12-64-73-94-107-128-sest-sonetu-v-mem-prekladu

https://ucbcluj.org/current-issue/vol-21-spring-2012/2842-2/

http://mikechasar.blogspot.cz/2011/02/gi-jane-dh-lawrence.html

Shakespeare forever!

Domácí úkol:

Vyhledejte jakýkoli český překlad své oblíbené básně a anglický originál spolu s českou verzí vlože do komentáře k tomuto blogu.

Naučte se alespoň 8 řádek zpaměti - česky i anglicky. Zkuste si recitaci před zrcadlem, vnímejte rytmus básně, porovnávejte básnické prostředky použité v originále a v překladu.

Vyhledejte jakýkoli český překlad své oblíbené básně a anglický originál spolu s českou verzí vlože do komentáře k tomuto blogu.

Naučte se alespoň 8 řádek zpaměti - česky i anglicky. Zkuste si recitaci před zrcadlem, vnímejte rytmus básně, porovnávejte básnické prostředky použité v originále a v překladu.

23. října 2017

Stylové roviny

Představte si čtyři zcela odlišné postavy. Jak by která z nich formulovala tyto dvě věty?

Pes vyskočil na gauč.

Postavili jsme dům.

Vložte své návrhy + označení postav do komentářů.

Série synonym najdete například zde:

http://prekladanipvk.blogspot.cz/2016/02/synonymie-stylove-roviny.html

http://prekladanipvk.blogspot.cz/2014/10/stylove-roviny.html

Pes vyskočil na gauč.

Postavili jsme dům.

Vložte své návrhy + označení postav do komentářů.

Série synonym najdete například zde:

http://prekladanipvk.blogspot.cz/2016/02/synonymie-stylove-roviny.html

http://prekladanipvk.blogspot.cz/2014/10/stylove-roviny.html

19. října 2017

Jak je důležité míti Filipa

Konverzační komedie Oscara Wildea se stala legendou i na české scéně, mimo jiné i zásluhou skvělé inscenace Vinohradského divadla. (ukázka zde) Překlad v takových případech hraje roli naprosto zásadní!

Copyright je věčný problém...

1. Seznamte se pečlivě s celým dílem v originále. Přečtete si více o autorovi i jeho divadelní hře. Seznamte se s jednajícími postavami a se synopsí celého příběhu.

Guttenberg fulltext

2. Následující ukázka je ze závěru komedie a přináší rozuzlení celého příběhu. Přečtěte si nejprve pečlivě celý text, soustřeďte se na charakterizaci jednotlivých postav. Poté začněte překládat vyznačenou část textu.

__________________________

Copyright je věčný problém...

1. Seznamte se pečlivě s celým dílem v originále. Přečtete si více o autorovi i jeho divadelní hře. Seznamte se s jednajícími postavami a se synopsí celého příběhu.

Guttenberg fulltext

2. Následující ukázka je ze závěru komedie a přináší rozuzlení celého příběhu. Přečtěte si nejprve pečlivě celý text, soustřeďte se na charakterizaci jednotlivých postav. Poté začněte překládat vyznačenou část textu.

__________________________

The Importance of Being Earnest

A Trivial

Comedy for Serious People

Oscar Wilde

Lady Bracknell.

[Starting.] Miss Prism! Did I hear you mention a Miss Prism?

Chasuble. Yes, Lady

Bracknell. I am on my way to join her.

Lady Bracknell. Pray

allow me to detain you for a moment.

This matter may prove to be one of vital importance to Lord Bracknell

and myself. Is this Miss Prism a female

of repellent aspect, remotely connected with education?

Chasuble. [Somewhat

indignantly.] She is the most cultivated

of ladies, and the very picture of respectability.

Lady Bracknell. It is

obviously the same person. May I ask

what position she holds in your household?

Chasuble.

[Severely.] I am a celibate,

madam.

Jack.

[Interposing.] Miss Prism, Lady

Bracknell, has been for the last three years Miss Cardew's esteemed governess

and valued companion.

Lady Bracknell. In

spite of what I hear of her, I must see her at once. Let her be sent for.

Chasuble. [Looking

off.] She approaches; she is nigh.

[Enter Miss Prism hurriedly.]

Miss Prism. I was told

you expected me in the vestry, dear Canon.

I have been waiting for you there for an hour and three-quarters. [Catches sight of Lady Bracknell, who has

fixed her with a stony glare. Miss Prism

grows pale and quails. She looks

anxiously round as if desirous to escape.]

Lady Bracknell. [In a

severe, judicial voice.] Prism! [Miss Prism bows her head in shame.] Come here, Prism! [Miss Prism approaches in a humble

manner.] Prism! Where is that baby? [General consternation. The Canon starts back in horror. Algernon and Jack pretend to be anxious to shield

Cecily and Gwendolen from hearing the details of a terrible public scandal.] Twenty-eight years ago, Prism, you left Lord

Bracknell's house, Number 104, Upper Grosvenor Street, in charge of a

perambulator that contained a baby of the male sex. You never returned. A few weeks later, through the elaborate

investigations of the Metropolitan police, the perambulator was discovered at midnight,

standing by itself in a remote corner of Bayswater. It contained the manuscript of a three-volume

novel of more than usually revolting sentimentality. [Miss Prism starts in involuntary

indignation.] But the baby was not

there! [Every one looks at Miss Prism.]

Prism! Where is that baby? [A pause.]

Miss Prism. Lady Bracknell, I admit with shame that I do

not know. I only wish I did. The plain facts of the case are these. On the morning of the day you mention, a day

that is for ever branded on my memory, I prepared as usual to take the baby out

in its perambulator. I had also with me

a somewhat old, but capacious hand-bag in which I had intended to place the

manuscript of a work of fiction that I had written during my few unoccupied

hours. In a moment of mental

abstraction, for which I never can forgive myself, I deposited the manuscript

in the basinette, and placed the baby in the hand-bag.

Jack. [Who has been listening attentively.] But where did you deposit the hand-bag?

Miss Prism. Do not ask me, Mr. Worthing.

Jack. Miss Prism, this is a matter of no small

importance to me. I insist on knowing

where you deposited the hand-bag that contained that infant.

Miss Prism. I left it in the cloak-room of one of the

larger railway stations in London.

Jack. What railway station?

Miss Prism. [Quite crushed.] Victoria.

The Brighton line. [Sinks into a

chair.]

Jack. I must retire to my room for a moment. Gwendolen, wait here for me.

Gwendolen. If you are not too long, I will wait here for

you all my life. [Exit Jack in great

excitement.]

Chasuble. What do you think this means, Lady Bracknell?

Lady Bracknell. I dare not even suspect, Dr. Chasuble. I need hardly tell you that in families of

high position strange coincidences are not supposed to occur. They are hardly considered the thing.

[Noises heard

overhead as if some one was throwing trunks about. Every one looks up.]

Cecily. Uncle Jack seems strangely agitated.

Chasuble. Your guardian has a very emotional nature.

Lady Bracknell. This noise is extremely unpleasant. It sounds as if he was having an

argument. I dislike arguments of any

kind. They are always vulgar, and often

convincing.

Chasuble. [Looking up.]

It has stopped now. [The noise is

redoubled.]

Lady Bracknell. I wish he would arrive at some conclusion.

Gwendolen. This suspense is terrible. I hope it will last. [Enter Jack with a hand-bag of black leather

in his hand.]

Jack. [Rushing over to Miss Prism.] Is this the hand-bag, Miss Prism? Examine it

carefully before you speak. The

happiness of more than one life depends on your answer.

Miss Prism. [Calmly.]

It seems to be mine. Yes, here is

the injury it received through the upsetting of a Gower Street omnibus in

younger and happier days. Here is the

stain on the lining caused by the explosion of a temperance beverage, an

incident that occurred at Leamington.

And here, on the lock, are my initials.

I had forgotten that in an extravagant mood I had had them placed

there. The bag is undoubtedly mine. I am delighted to have it so unexpectedly

restored to me. It has been a great

inconvenience being without it all these years.

Jack. [In a pathetic voice.] Miss Prism, more is restored to you than this

hand-bag. I was the baby you placed in

it.

Miss Prism. [Amazed.]

You?

Jack. [Embracing her.] Yes . . . mother!

Miss Prism. [Recoiling in indignant astonishment.] Mr. Worthing!

I am unmarried!

Jack. Unmarried!

I do not deny that is a serious blow.

But after all, who has the right to cast a stone against one who has

suffered? Cannot repentance wipe out an

act of folly? Why should there be one

law for men, and another for women?

Mother, I forgive you. [Tries to

embrace her again.]

Miss Prism. [Still more indignant.] Mr. Worthing, there is some error. [Pointing

to Lady Bracknell.] There is the lady

who can tell you who you really are.

Jack. [After a pause.] Lady Bracknell, I hate to seem inquisitive,

but would you kindly inform me who I am?

Lady Bracknell. I am afraid that the news I have to give you

will not altogether please you. You are

the son of my poor sister, Mrs. Moncrieff, and consequently Algernon's elder

brother.

Jack. Algy's elder brother! Then I have a brother after all. I knew I had a brother! I always said I had a brother! Cecily,--how could you have ever doubted that

I had a brother? [Seizes hold of

Algernon.] Dr. Chasuble, my unfortunate

brother. Miss Prism, my unfortunate

brother. Gwendolen, my unfortunate brother.

Algy, you young scoundrel, you will have to treat me with more respect

in the future. You have never behaved to

me like a brother in all your life.

Algernon. Well, not till to-day, old boy, I admit. I did my best, however, though I was out of

practice.

[Shakes hands.]

Gwendolen. [To Jack.]

My own! But what own are

you? What is your Christian name, now

that you have become some one else?

Jack. Good heavens! .

. . I had quite forgotten that point.

Your decision on the subject of my name is irrevocable, I suppose?

Gwendolen. I never

change, except in my affections.

Cecily. What a noble

nature you have, Gwendolen!

Jack. Then the

question had better be cleared up at once.

Aunt Augusta, a moment. At the

time when Miss Prism left me in the hand-bag, had I been christened already?

Lady Bracknell. Every

luxury that money could buy, including christening, had been lavished on you by

your fond and doting parents.

Jack. Then I was

christened! That is settled. Now, what name was I given? Let me know the worst.

Lady Bracknell. Being

the eldest son you were naturally christened after your father.

Jack.

[Irritably.] Yes, but what was my

father's Christian name?

Lady Bracknell.

[Meditatively.] I cannot at the

present moment recall what the General's Christian name was. But I have no doubt he had one. He was

eccentric, I admit. But only in later

years. And that was the result of the

Indian climate, and marriage, and indigestion, and other things of that kind.

Jack. Algy! Can't you recollect what our father's

Christian name was?

Algernon. My dear

boy, we were never even on speaking terms.

He died before I was a year old.

Jack. His name would

appear in the Army Lists of the period, I suppose, Aunt Augusta?

Lady Bracknell. The

General was essentially a man of peace, except in his domestic life. But I have no doubt his name would appear in

any military directory.

Jack. The Army Lists

of the last forty years are here. These

delightful records should have been my constant study. [Rushes to bookcase and tears the books

out.] M. Generals . . . Mallam, Maxbohm,

Magley, what ghastly names they have--Markby, Migsby, Mobbs, Moncrieff! Lieutenant 1840, Captain, Lieutenant-Colonel,

Colonel, General 1869, Christian names, Ernest John. [Puts book very quietly down and speaks quite

calmly.] I always told you, Gwendolen,

my name was Ernest, didn't I? Well, it is Ernest after all. I mean it naturally is Ernest.

Lady Bracknell. Yes,

I remember now that the General was called Ernest, I knew I had some particular

reason for disliking the name.

Gwendolen.

Ernest! My own Ernest! I felt from the first that you could have no

other name!

Jack. Gwendolen, it

is a terrible thing for a man to find out suddenly that all his life he has

been speaking nothing but the truth. Can

you forgive me?

Gwendolen. I

can. For I feel that you are sure to

change.

Jack. My own one!

Chasuble. [To Miss

Prism.] Laetitia! [Embraces her]

Miss Prism.

[Enthusiastically.]

Frederick! At last!

Algernon.

Cecily! [Embraces her.] At last!

Jack. Gwendolen! [Embraces her.] At last!

Lady Bracknell. My

nephew, you seem to be displaying signs of

triviality.

Jack. On the

contrary, Aunt Augusta, I've now realised for the first

time in my life the vital Importance of Being Earnest.

TABLEAU

5. října 2017

Vizualizace

Dobře napsané vyprávění vyvolává ve čtenáři pocit, jako by se vydával s postavami na jejich cestu, viděl okolní svět jejich očima. Dnes budeme putovat do viktoriánské Anglie a prohlédneme si ji pohledem Jany Eyrové.

1. Přečtete si celý následující úryvek. Soustřeďte se na popis postav a prostředí, představujte si jednotlivé scény jako obrazy. Prožívejte s Janou první příjezd do Thornfieldu.

Vraťte se do reality - a vyhledejte si informace o autorce i díle, přečte si literární analýzy a kritiky. Nepodceňujte tuto překladatelskou přípravu! Usnadní vám samotnou práci s textem.

2. Začněte překládat označenou část. Nejprve si znovu vybavte obrazy, vykreslete si v duchu dům i krajinu, pak teprve začněte tvořit text, který stejný obraz přinese čtenářům.

Charlotte Bronte

Jane Eyre (fulltext available free at Project Guttenberg)

1. Přečtete si celý následující úryvek. Soustřeďte se na popis postav a prostředí, představujte si jednotlivé scény jako obrazy. Prožívejte s Janou první příjezd do Thornfieldu.

Vraťte se do reality - a vyhledejte si informace o autorce i díle, přečte si literární analýzy a kritiky. Nepodceňujte tuto překladatelskou přípravu! Usnadní vám samotnou práci s textem.

2. Začněte překládat označenou část. Nejprve si znovu vybavte obrazy, vykreslete si v duchu dům i krajinu, pak teprve začněte tvořit text, který stejný obraz přinese čtenářům.

CHAPTER XI

A new chapter in a novel is something like a new scene in a

play; and when I draw up the curtain this time, reader, you must fancy you see

a room in the George Inn at Millcote, with such large figured papering on the

walls as inn rooms have; such a carpet, such furniture, such ornaments on the

mantelpiece, such prints, including a portrait of George the Third, and another

of the Prince of Wales, and a representation of the death of Wolfe. All this is visible to you by the light of an

oil lamp hanging from the ceiling, and by that of an excellent fire, near which

I sit in my cloak and bonnet; my muff and umbrella lie on the table, and I am

warming away the numbness and chill contracted by sixteen hours' exposure to the

rawness of an October day: I left Lowton at four o'clock a.m., and the Millcote

town clock is now just striking eight.

Reader, though I look comfortably accommodated, I am not

very tranquil in my mind. I thought when

the coach stopped here there would be some one to meet me; I looked anxiously

round as I descended the wooden steps the "boots" placed for my

convenience, expecting to hear my name pronounced, and to see some description

of carriage waiting to convey me to

Thornfield. Nothing

of the sort was visible; and when I asked a waiter if any one had been to

inquire after a Miss Eyre, I was answered in the negative: so I had no resource

but to request to be shown into a private room: and here I am waiting, while

all sorts of doubts and fears are troubling my thoughts.

It is a very strange sensation to inexperienced youth to

feel itself quite alone in the world, cut adrift from every connection,

uncertain whether the port to which it is bound can be reached, and prevented

by many impediments from returning to that it has quitted. The charm of adventure sweetens that

sensation, the glow of pride warms it; but then the throb of fear disturbs it;

and fear with me became predominant when half-an-hour elapsed and still I was

alone. I bethought myself to ring the

bell.

"Is there a place in this neighbourhood called

Thornfield?" I asked of the waiter who answered the summons.

"Thornfield? I

don't know, ma'am; I'll inquire at the bar." He vanished, but reappeared instantly--

"Is your name Eyre, Miss?"

"Yes."

"Person here waiting for you."

I jumped up, took my muff and umbrella, and hastened into

the inn-passage: a man was standing by the open door, and in the lamp-lit street

I dimly saw a one-horse conveyance.

"This will be your luggage, I suppose?" said the

man rather abruptly when he saw me, pointing to my trunk in the passage.

"Yes." He

hoisted it on to the vehicle, which was a sort of car, and then I got in;

before he shut me up, I asked him how far it was to Thornfield.

"A matter of six miles."

"How long shall we be before we get there?"

"Happen an hour and a half."

He fastened the car door, climbed to his own seat outside,

and we set off. Our progress was

leisurely, and gave me ample time to reflect; I was content to be at length so

near the end of my journey; and as I leaned back in the comfortable though not

elegant conveyance, I meditated much at my ease.

"I suppose," thought I, "judging from the

plainness of the servant and carriage, Mrs. Fairfax is not a very dashing

person: so much the better; I never lived amongst fine people but once, and I

was very miserable with them. I wonder

if she lives alone except this little girl; if so, and if she is in any degree

amiable, I shall surely be able to get on with her; I will do my best; it is a

pity that doing one's best does not always answer. At Lowood, indeed, I took that resolution,

kept it, and succeeded in pleasing; but with Mrs. Reed, I remember my best was

always spurned with scorn. I pray God

Mrs. Fairfax may not turn out a second Mrs. Reed; but if she does, I am not

bound to stay with her! let the worst come to the worst, I can advertise

again. How far are we on our road now, I

wonder?"

I let down the window and looked out; Millcote was behind us;

judging by the number of its lights, it seemed a place of considerable

magnitude, much larger than Lowton. We

were now, as far as I could see, on a sort of common; but there were houses

scattered all over the district; I felt we were in a different region to

Lowood, more populous, less picturesque; more stirring, less romantic.

The roads were heavy, the night misty; my conductor let his

horse walk all the way, and the hour and a half extended, I verily believe, to

two hours; at last he turned in his seat and said--

"You're noan so far fro' Thornfield now."

Again I looked out: we were passing a church; I saw its low

broad tower against the sky, and its bell was tolling a quarter; I saw a narrow

galaxy of lights too, on a hillside, marking a village or hamlet. About ten minutes after, the driver got down

and opened a pair of gates: we passed through, and they clashed to behind

us. We now slowly ascended a drive, and

came upon the long front of a house: candlelight gleamed from one curtained

bow-window; all the rest were dark. The

car stopped at the front door; it was opened by a maid-servant; I alighted and

went in.

"Will you walk this way, ma'am?" said the girl;

and I followed her across a square hall with high doors all round: she ushered

me into a room whose double illumination of fire and candle at first dazzled

me, contrasting as it did with the darkness to which my eyes had been for two

hours inured; when I could see, however, a cosy and agreeable picture presented

itself to my view.

A snug small room; a round table by a cheerful fire; an

arm-chair high- backed and old-fashioned, wherein sat the neatest imaginable

little elderly lady, in widow's cap, black silk gown, and snowy muslin apron; exactly

like what I had fancied Mrs. Fairfax, only less stately and milder

looking. She was occupied in knitting; a

large cat sat demurely at her feet; nothing in short was wanting to complete

the beau-ideal of domestic comfort. A

more reassuring introduction for a new governess could scarcely be conceived;

there was no grandeur to overwhelm, no stateliness to embarrass; and then, as I

entered, the old lady got up and promptly and kindly came forward to meet me.

"How do you do, my dear? I am afraid you have had a tedious ride; John

drives so slowly; you must be cold, come to the fire."

"Mrs. Fairfax, I suppose?" said I.

"Yes, you are right: do sit down."

She conducted me to her own chair, and then began to remove

my shawl and untie my bonnet-strings; I begged she would not give herself so

much trouble.

"Oh, it is no trouble; I dare say your own hands are

almost numbed with cold. Leah, make a

little hot negus and cut a sandwich or two: here are the keys of the

storeroom."

And she produced from

her pocket a most housewifely bunch of keys, and delivered them to the servant.

"Now, then, draw nearer to the fire," she

continued. "You've brought your

luggage with you, haven't you, my dear?"

"Yes, ma'am."

"I'll see it carried into your room," she said,

and bustled out.

"She treats me

like a visitor," thought I. "I

little expected such a reception; I anticipated only coldness and stiffness:

this is not like what I have heard of the treatment of governesses; but I must

not exult too soon."

She returned; with her own hands cleared her knitting

apparatus and a book or two from the table, to make room for the tray which

Leah now brought, and then herself handed me the refreshments. I felt rather confused at being the object of

more attention than I had ever before received, and, that too, shown by my

employer and superior; but as she did not herself seem to consider she was

doing anything out of her place, I thought it better to take her civilities

quietly.

"Shall I have the pleasure of seeing Miss Fairfax

to-night?" I asked, when I had partaken of what she offered me.

"What did you

say, my dear? I am a little deaf,"

returned the good lady, approaching her ear to my mouth.

I repeated the question more distinctly.

"Miss Fairfax?

Oh, you mean Miss Varens! Varens

is the name of your future pupil."

"Indeed! Then

she is not your daughter?"

"No,--I have no family."

I should have followed up my first inquiry, by asking in

what way Miss Varens was connected with her; but I recollected it was not

polite to ask too many questions: besides, I was sure to hear in time.

"I am so glad," she continued, as she sat down

opposite to me, and took the cat on her knee; "I am so glad you are come;

it will be quite pleasant living here now with a companion. To be sure it is pleasant at any time; for

Thornfield is a fine old hall, rather neglected of late years perhaps, but

still it is a respectable place; yet you know in winter-time one feels dreary

quite alone in the best quarters. I say alone--Leah

is a nice girl to be sure, and John and his wife are very decent people; but

then you see they are only servants, and one can't converse with them on terms

of equality: one must keep them at due distance, for fear of losing one's

authority. I'm sure last winter (it was

a very severe one, if you recollect, and when it did not snow, it rained and

blew), not a creature but the butcher and postman came to the house, from

November till February; and I really got quite melancholy with sitting night

after night alone; I had Leah in to read to me sometimes; but I don't think the

poor girl liked the task much: she felt it confining. In spring and summer one got on better:

sunshine and long days make such a difference; and then, just at the

commencement of this autumn, little Adela Varens came and her nurse: a child

makes a house alive all at once; and now you are here I shall be quite

gay."

My heart really warmed to the worthy lady as I heard her

talk; and I drew my chair a little nearer to her, and expressed my sincere wish

that she might find my company as agreeable as she anticipated.

"But I'll not keep you sitting up late to-night,"

said she; "it is on the stroke of twelve now, and you have been travelling

all day: you must feel tired. If you

have got your feet well warmed, I'll show you your bedroom. I've had the room next to mine prepared for

you; it is only a small apartment, but I thought you would like it better than

one of the large front chambers: to be sure they have finer furniture, but they

are so dreary and solitary, I never sleep in them myself."

I thanked her for her considerate choice, and as I really

felt fatigued with my long journey, expressed my readiness to retire. She took her candle, and I followed her from

the room. First she went to see if the hall-door

was fastened; having taken the key from the lock, she led the way

upstairs. The steps and banisters were

of oak; the staircase window was high and latticed; both it and the long gallery

into which the bedroom doors opened looked as if they belonged to a church

rather than a house. A very chill and

vault-like air pervaded the stairs and gallery, suggesting cheerless ideas of

space and solitude; and I was glad, when finally ushered into my chamber, to

find it of small dimensions, and furnished in ordinary, modern style.

When Mrs. Fairfax had bidden me a kind good-night, and I had

fastened my door, gazed leisurely round, and in some measure effaced the eerie impression

made by that wide hall, that dark and spacious staircase, and that long, cold

gallery, by the livelier aspect of my little room, I remembered that, after a

day of bodily fatigue and mental anxiety, I was now at last in safe haven. The impulse of gratitude swelled my heart, and

I knelt down at the bedside, and offered up thanks where thanks were due; not

forgetting, ere I rose, to implore aid on my further path, and the power of

meriting the kindness which seemed so frankly offered me before it was

earned. My couch had no thorns in it

that night; my solitary room no fears.

At once weary and content, I slept soon and soundly: when I awoke it was

broad day.

The chamber looked such a bright little place to me as the

sun shone in between the gay blue chintz window curtains, showing papered walls

and a carpeted floor, so unlike the bare planks and stained plaster of Lowood, that

my spirits rose at the view. Externals

have a great effect on the young: I thought that a fairer era of life was

beginning for me, one that was to have its flowers and pleasures, as well as

its thorns and toils. My faculties, roused by the change of scene, the new

field offered to hope, seemed all astir.

I cannot precisely define what they expected, but it was something

pleasant: not perhaps that day or that month, but at an indefinite future

period.

I rose; I dressed myself with care: obliged to be plain--for

I had no article of attire that was not

made with extreme simplicity--I was still by nature solicitous to be neat. It was not my habit to be disregardful of

appearance or careless of the impression I made: on the contrary, I ever wished

to look as well as I could, and to please as much as my want of beauty would

permit. I sometimes regretted that I was

not handsomer; I sometimes wished to have rosy cheeks, a straight nose, and

small cherry mouth; I desired to be tall, stately, and finely developed in

figure; I felt it a misfortune that I was so little, so pale, and had features

so irregular and so marked. And why had

I these aspirations and these regrets?

It would be difficult to say: I could not then distinctly say it to

myself; yet I had a reason, and a logical, natural reason too. However, when I

had brushed my hair very smooth, and put on my black

frock--which,

Quakerlike as it was, at least had the merit of fitting to a nicety--and

adjusted my clean white tucker, I thought I should do respectably enough to

appear before Mrs. Fairfax, and that my new pupil would not at least recoil

from me with antipathy. Having opened my

chamber window, and seen that I left all things straight and neat on the toilet

table, I ventured forth.

Traversing the long

and matted gallery, I descended the slippery steps of oak; then I gained the

hall: I halted there a minute; I looked at some pictures on the walls (one, I

remember, represented a grim man in a cuirass, and one a lady with powdered

hair and a pearl necklace), at a bronze lamp pendent from the ceiling, at a

great clock whose case was of oak curiously carved, and ebon black with time

and rubbing. Everything appeared very

stately and imposing to me; but then I was so little accustomed to

grandeur. The hall-door, which was half

of glass, stood open; I stepped over the threshold. It was a fine autumn morning; the early sun

shone serenely on embrowned groves and still green fields; advancing on to the

lawn, I looked up and surveyed the front of the mansion. It was three storeys high, of proportions not

vast, though considerable: a gentleman's manor-house, not a nobleman's seat:

battlements round the

top gave it a picturesque look. Its grey

front stood out well from the background of a rookery, whose cawing tenants were

now on the wing: they flew over the lawn and grounds to alight in a great

meadow, from which these were separated by a sunk fence, and where an array of

mighty old thorn trees, strong, knotty, and broad as oaks, at once explained

the etymology of the mansion's designation.

Farther off were hills: not so lofty as those round Lowood, nor so

craggy, nor so like barriers of separation from the living world; but yet quiet

and lonely hills enough, and seeming to embrace Thornfield with a seclusion I

had not expected to

find existent so near the stirring locality of Millcote. A little hamlet, whose roofs were blent with

trees, straggled up the side of one of these hills; the church of the district

stood nearer Thornfield: its old tower-top looked over a knoll between the house

and gates.

I was yet enjoying

the calm prospect and pleasant fresh air, yet listening with delight to the

cawing of the rooks, yet surveying the wide, hoary front of the hall, and

thinking what a great place it was for one lonely little dame like Mrs. Fairfax

to inhabit, when that lady appeared at the door.

"What! out already?" said she. "I see you are an early

riser." I went up to her, and was

received with an affable kiss and shake of the hand.

"How do you like Thornfield?" she asked. I told her I liked it very much.

"Yes," she said, "it is a pretty place; but I

fear it will be getting out of order, unless Mr. Rochester should take it into

his head to come and reside here permanently; or, at least, visit it rather

oftener: great houses and fine grounds require the presence of the proprietor."

"Mr. Rochester!" I exclaimed. "Who is he?"

"The owner of Thornfield," she responded

quietly. "Did you not know he was

called Rochester?"

21. září 2017

Jižanský monolog

1. Pečlivě si přečtěte celý úryvek. Kompletní text najdete v Projektu Guttenberg.

2. Vypište si výrazy a obraty, které neznáte. Při hledání jejich významu pokaždé kontrolujte výsledek ve více zdrojích.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/

http://www.urbandictionary.com/

http://www.slovnik.cz/

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/

http://dictionary.cambridge.org/

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/

http://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/

http://www.wisegeek.com/

3. Přeložte tučně vyznačenou část textu a překlad vložte do komentáře k tomuto blogu.

__________________________________

2. Vypište si výrazy a obraty, které neznáte. Při hledání jejich významu pokaždé kontrolujte výsledek ve více zdrojích.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/

http://www.urbandictionary.com/

http://www.slovnik.cz/

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/

http://dictionary.cambridge.org/

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/

http://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/

http://www.wisegeek.com/

3. Přeložte tučně vyznačenou část textu a překlad vložte do komentáře k tomuto blogu.

__________________________________

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens)

CHAPTER I

"TOM!"

No answer.

"TOM!"

No answer.

"What's gone with that boy, I wonder? You

TOM!"

No answer.

The old lady pulled her spectacles down and looked over them

about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them. She seldom or never

looked _through_ them for so small a thing as a boy; they were her state pair,

the pride of her heart, and were built for "style," not

service-she could have seen through a pair of stove-lids

just as well. She looked perplexed for a moment, and then said, not fiercely,

but still loud enough for the furniture to hear:

"Well, I lay if I get hold of you I'll-"

She did not finish, for by this time she was bending down

and punching under the bed with the broom, and so she needed breath to

punctuate the punches with. She resurrected nothing but the cat.

"I never did see the beat of that boy!"

She went to the open door and stood in it and looked out

among the tomato vines and "jimpson" weeds that constituted the

garden. No Tom. So she lifted up her voice at an angle calculated for distance

and shouted:

"Y-o-u-u TOM!"

There was a slight noise behind her and she turned just in

time to seize a small boy by the slack of his roundabout and arrest his flight.

"There! I might 'a' thought of that closet. What you been doing in there?"

"Nothing."

"Nothing! Look at your hands. And look at your mouth.

What _is_ that truck?"

"I don't know, aunt."

"Well, I know. It's jam-that's what it is. Forty times

I've said if you didn't let that jam alone I'd skin you. Hand me that

switch."

The switch hovered in the air-the peril was desperate. "My!

Look behind you, aunt!"

The old lady whirled round, and snatched her skirts out of

danger. The lad fled on the instant, scrambled up the high board-fence, and disappeared

over it.

His aunt Polly stood surprised a moment, and then broke into

a gentle laugh.

"Hang the boy, can't I never learn anything? Ain't he

played me tricks enough like that for me to be looking out for him by this

time? But old fools is the biggest fools there is. Can't learn an old dog new

tricks, as the saying is. But my goodness, he never plays them alike, two days,

and how is a body to know what's coming? He 'pears to know just how long he can

torment me before I get my dander up, and he knows if he can make out to put me

off for a minute or make me laugh, it's all down again and I can't hit him a

lick. I ain't doing my duty by that boy, and that's the Lord's truth, goodness

knows. Spare the rod and spile the child, as the Good Book says. I'm a laying

up sin and suffering for us both, I know. He's full of the Old Scratch, but

laws-a-me! he's my own dead sister's boy, poor thing, and I ain't got the heart

to lash him, somehow. Every time I let him off, my conscience does hurt me so,

and every time I hit him my old heart most breaks. Well-a-well, man that is born

of woman is of few days and full of trouble, as the Scripture says, and I

reckon it's so. He'll play hookey this evening, and I'll just be obleeged to

make him work, tomorrow, to punish him. It's mighty hard to make him work

Saturdays, when all the boys is having holiday, but he hates work more than he hates

anything else, and I've _got_ to do some of my duty by him, or I'll be the

ruination of the child."

29. března 2017

Science fiction

2010:

Odyssey two

Arthur

C. Clarke (1982)

Author's Note

The

novel 2001: A Space Odyssey was written during the years 1964-8 and was published

in July 1968, shortly after release of the movie. As I have described in The

Lost Worlds of 2001, both projects proceeded simultaneously, with feedback in

each direction. Thus I often had the strange experience of revising the

manuscript after viewing rushes based upon an earlier version of the story a stimulating,

but rather expensive, way of writing a novel.

….

The

Saturnian system was reached via Jupiter: Discovery made a close approach to

the giant planet, using its enormous gravitational field

to produce a 'slingshot' effect and to accelerate it along the second lap of

its journey. Exactly the same manoeuvre was used by the Voyager space probes in

1979, when they made the first detailed reconnaissance of the outer giants.

…

No

one could have imagined, back in the mid-sixties, that the exploration of the

moons of Jupiter lay, not in the next century, but only fifteen years ahead. Nor

had anyone dreamed of the wonders that would be found there - although we can

be quite certain that the discoveries of the twin Voyagers will one day be surpassed

by even more unexpected finds. When 2001 was written, Io, Europa, Ganymede,

and Callisto were mere pinpoints of light in even the most powerful telescope;

now they are worlds, each unique, and one of them - Io - is the most volcanically

active body in the Solar System.

…

2001

was written in an age that now lies beyond one of the Great Divides in human

history; we are sundered from it forever by the moment when Neil Armstrong set

foot upon the Moon. The date 20 July 1969 was still half a decade in the future

when Stanley Kubrick and I started thinking about the 'proverbial good

science-fiction movie' (his phrase). Now history and fiction have become

inextricably intertwined. The Apollo astronauts had already seen the film when

they left for the Moon.

The

crew of Apollo 8, who at Christmas 1968 became the first men ever to set eyes

upon the Lunar Farside, told me that they had been tempted to radio back the

discovery of a large black monolith: alas, discretion prevailed.

And

there were, later, almost uncanny instances of nature imitating art. Strangest

of all was the saga of Apollo 13 in 1970.

As

a good opening, the Command Module, which houses the crew, had been christened

Odyssey, Just before the explosion of the oxygen tank that caused the mission

to be aborted, the crew had been playing Richard Strauss's Zarathustra theme,

now universally identified with the movie. Immediately after the loss of power,

Jack Swigert radioed back to Mission Control: 'Houston, we've had a

problem.'

The words that Hal used to astronaut Frank Poole on a similar occasion were:

'Sorry to interrupt the festivities, but we have a problem.'

When

the report of the Apollo 13 mission was later published, NASA Administrator Tom

Paine sent me a copy, and noted under Swigert's words: 'Just as you always said

it would be, Arthur.' I still get a very strange feeling when I contemplate

this whole series of events - almost, indeed, as if I share a certain

responsibility.

…

Inevitably,

therefore, the story you are about to read is something much more complex than

a straightforward sequel to the earlier novel - or the movie. Where these

differ, I have followed the screen version; however, I have been more concerned

with making this book self-consistent, and as accurate as possible in the light

of current knowledge.

Which,

of course, will once more be out of date by 2001...

Arthur

C. Clarke

COLOMBO,

SRI LANKA

JANUARY

1982

I

LEONOV

1

Meeting

at the Focus

Even

in this metric age, it was still the thousand-foot telescope, not the three-hundred-metre

one. The great saucer set among the mountains was already half full of shadow,

as the tropical sun dropped swiftly to rest, but the triangular raft of the

antenna complex suspended high above its centre still blazed with light. From

the ground far below, it would have taken keen eyes to notice the two human

figures in the aerial maze of girders, support cables, and wave-guides.

'The

time has come,' said Dr Dimitri Moisevitch to his old friend Heywood Floyd, 'to

talk of many things. Of shoes and spaceships and sealing wax, but mostly of

monoliths and malfunctioning computers.'

'So

that's why you got me away from the conference. Not that I really mind I've heard

Carl give that SETI speech so many times that I can recite it myself. And the

view certainly is fantastic - you know, all the times I've been to Arecibo,

I've never made it up here to the antenna feed.'

'Shame

on you. I've been here three times. Imagine - we're listening to the whole

universe - but no one can overhear us. So let's talk about your problem.'

'What

problem?'

'To

start with, why you had to resign as Chairman of the National Council on Astronautics.'

'I

didn't resign. The University of Hawaii pays a lot better.'

'Okay

- you didn't resign - you were one jump ahead of them. After all these years,

Woody, you can't fool me, and you should give up trying. If they offered the

NCA back to you right now, would you hesitate?'

'All

right, you old Cossak. What do you want to know?'

'First

of all, there are lots of loose ends in the report you finally issued after so

much prodding. We'll overlook the ridiculous and frankly illegal secrecy with

which your people dug up the Tycho monolith -'

'That

wasn't my idea.'

'Glad

to hear it: I even believe you. And we appreciate the fact that you're now

letting everyone examine the thing - which of course is what you should have done

in the first place. Not that it's done much good...'

There

was a gloomy silence while the two men contemplated the black enigma up there

on the Moon, still contemptuously defying all the weapons that human ingenuity

could bring to bear upon it. Then the Russian scientist continued.

'Anyway,

whatever the Tycho monolith may be, there's something more important out at

Jupiter. That's where it sent its signal, after all. And that's where your

people ran into trouble. Sorry about that, by the way - though Frank Poole was

the only one I knew personally. Met him at the '98 IAF Congress – he seemed a

good man.'

'Thank

you; they were all good men. I wish we knew what happened to them.'

'Whatever

it was, surely you'll admit that it now concerns the whole human race - not

merely the United States. You can no longer try to use your knowledge for

purely national advantage.'

'Dimitri

- you know perfectly well that your side would have done exactly the same

thing. And you'd have helped.'

'You're

absolutely right. But that's ancient history - like the just departed administration

of yours that was responsible for the whole mess. With a new President, perhaps

wiser counsels will prevail.'

'Possibly.

Do you have any suggestions, and are they official or just personal hopes?'

'Entirely

unofficial at the moment. What the bloody politicians call exploratory talks.

Which I shall flatly deny ever occurred.'

'Fair

enough. Go on.'

'Okay

- here's the situation. You're assembling Discovery 2 in parking orbit as

quickly as you can, but you can't hope to have it ready in less than three years,

which means you'll miss the next launch window -,

'I

neither confirm nor deny. Remember I'm merely a humble university chancellor,

the other side of the world from the Astronautics Council.'

'And

your last trip to Washington was just a holiday to see old friends, I suppose.

To continue: our own Alexei Leonov -,

'I

thought you were calling it Gherman Titov.'

'Wrong,

Chancellor. The dear old CIA's let you down again. Leonov it is, as of last

January. And don't let anyone know I told you it will reach Jupiter at least a

year ahead of Discovery.'

'Don't

let anyone know I told you we were afraid of that. But do go on.'

'Because

my bosses are just as stupid and shortsighted as yours, they want to go it

alone. Which means that whatever went wrong with you may happen to us, and

we'll all be back to square one - or worse.'

'What

do you think went wrong? We're just as baffled as you are. And don't tell me

you haven't got all of Dave Bowman's transmissions.'

'Of

course we have. Right up to that last "My God, it's full of stars!" We've

even done a stress analysis on his voice patterns. We don't think he was hallucinating;

he was trying to describe what he actually saw.'

'And

what do you make of his doppler shift?'

'Completely

impossible, of course. When we lost his signal, he was receding at a tenth of

the speed of light. And he'd reached that in less than two minutes. A quarter

of a million gravities!'

'So

he must have been killed instantly.'

'Don't

pretend to be naive, Woody. Your space-pod radios aren't built to withstand

even a hundredth of that acceleration. If they could survive, so could Bowman -

at least, until we lost contact.'

'Just

doing an independent check on your deductions. From there on, we're as much in

the dark as you are. If you are.'

'Merely

playing with lots of crazy guesses I'd be ashamed to tell you. Yet none of

them, I suspect, will be half as crazy as the truth.'

In

small crimson explosions the navigation warning lights winked on all around

them, and the three slim towers supporting the antenna complex began to blaze

like beacons against the darkling sky. The last red sliver of the sun vanished

below the surrounding hills; Heywood Floyd waited for the Green Flash, which he

had never seen. Once again, he was disappointed.

'So,

Dimitri,' he said, 'let's get to the point. Just what are you driving at?'

'There

must be a vast amount of priceless information stored in Discovery's data

banks; presumably it's still being gathered, even though the ship's stopped transmitting.

We'd like to have that.'

'Fair

enough. But when you get out there, and Leonov makes a rendezvous, what's to

prevent you from boarding Discovery and copying everything you want?'

'I

never thought I'd have to remind you that Discovery is United States territory,

and an unauthorized entry would be piracy.'

'Except

in the event of a life-or-death emergency, which wouldn't be difficult to

arrange. After all, it would be hard for us to check what your boys were up to,

from a billion kilometres away.'

'Thanks

for the most interesting suggestion; I'll pass it on. But even if we went

aboard, it would take us weeks to learn all your systems, and read out all your

memory banks. What I propose is cooperation. I'm convinced that's the best idea

- but we may both have a job selling it to our respective bosses.'

'You

want one of our astronauts to fly with Leonov?'

'Yes

- preferably an engineer who's specialized in Discovery's systems. Like the

ones you're training at Houston to bring the ship home.'

'How

did you know that?'

'For

heaven's sake, Woody - it was on Aviation Week's videotext at least a month

ago.'

'I

am out of touch; nobody tells me what's been declassified.'

'All

the more reason to spend time in Washington. Will you back me up?'

'Absolutely.

I agree with you one hundred per cent. But -'

'But

what?'

'We

both have to deal with dinosaurs with brains in their tails. Some of mine will

argue: Let the Russians risk their necks, hurrying out to Jupiter. We'll be

there anyway a couple of years later - and what's the hurry?'

For

a moment there was silence on the antenna raft, except for a faint creak from

the immense supporting cables that held it suspended a hundred metres in the

sky. Then Moisevitch continued, so quietly that Floyd had to strain to hear him:

'Has anyone checked Discovery's orbit lately?'

'I

really don't know - but I suppose so. Anyway, why bother? It's a perfectly

stable one.'

'Indeed.

Let me tactlessly remind you of an embarrassing incident from the old NASA

days. Your first space station - Skylab. It was supposed to stay up at least a

decade, but you didn't do your calculations right. The air drag in the ionosphere

was badly underestimated, and it came down years ahead of schedule. I'm sure

you remember that little cliffhanger, even though you were a boy at the time.'

'It

was the year I graduated, and you know it. But Discovery doesn't go anywhere

near Jupiter. Even at perigee - er, perijove - it's much too high to be affected

by atmospheric drag.'

'I've

already said enough to get me exiled to my dacha again - and you might not be

allowed to visit me next time. So just ask your tracking people to do their job

more carefully, will you? And remind them that Jupiter has the biggest magnetosphere

in the Solar System.'

'I

understand what you're driving at - many thanks. Anything else before we go

down? I'm starting to freeze.'

'Don't

worry, old friend. As soon as you let all this filter through to Washington -

wait a week or so until I'm clear -things are going to get very, very hot.'

22. března 2017

Hudba a text

HW: registrujte si povídku k finálnímu překladu! Na capse jsou k dispozici soubory z díla E. Hemingwaye a R. Bradburyho.